The acquisition of bipedalism is considered to be a decisive step in human evolution.

Nevertheless, there is no consensus on its modalities and age, notably due to the lack of fossil remains. A research team, involving researchers from the CNRS, the University of Poitiers1 and their Chadian partners, examined three limb bones from the oldest human representative currently identified, Sahelanthropus tchadensis. Published in Nature on August 24, 2022, this study reinforces the idea of bipedalism being acquired very early in our history, at a time still associated with the ability to move on four limbs in trees.

At 7 million years old, Sahelanthropus tchadensis is considered the oldest representative species of humanity. Its description dates back to 2001 when the Franco-Chadian Paleoanthropological Mission (MPFT) discovered the remains of several individuals at Toros-Menalla in the Djurab Desert (Chad), including a very well-preserved cranium. This cranium, and in particular the orientation and anterior position of the occipital foramen where the vertebral column is inserted, indicates a mode of locomotion on two legs, suggesting that it was capable of bipedalism2.

In addition to the cranium, nicknamed Toumaï, and fragments of jaws and teeth that have already been published, the locality of Toros-Menalla 266 (TM 266) yielded two ulnae (forearm bone) and a femur (thigh bone). These bones were also attributed to Sahelanthropus because no other large primate was found at the site; however, it is impossible to know if they belong to the same individual as the cranium. Palaeontologists from the University of Poitiers, the CNRS, the University of N’Djamena and the National Centre of Research for Development (CNRD, Chad) published their complete analysis in Nature on August 24, 2022.

The femur and ulnae were subjected to a battery of measurements and analyses, concerning both their external morphology, and their internal structures using microtomography imaging: biometric measurements, geometric morphometrics, biomechanical indicators, etc. These data were compared to those of a relatively large sample of extant and fossil apes: chimpanzees, gorillas, orangutans, Miocene apes, and members of the human group (Orrorin, Ardipithecus, australopithecines, ancient Homo, Homo sapiens).

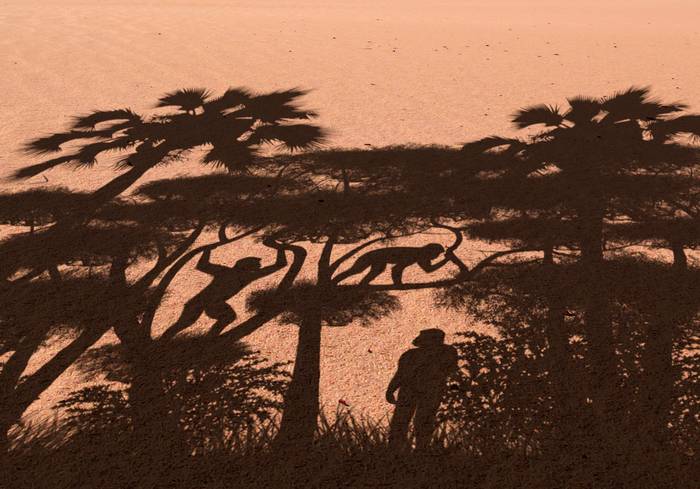

The structure of the femur indicates that Sahelanthropus was usually bipedal on the ground, but probably also in trees. According to results from the ulnae, this bipedalism coexisted in arboreal environments with a form of quadrupedalism, that is arboreal clambering enabled by firm hand grips, clearly differing from that of gorillas and chimpanzees who lean on the back of their phalanges.

The conclusions of this study, including the identification of habitual bipedalism, are based on the observation and comparison of more than twenty characteristics of the femur and ulnae. They are, by far, the most parsimonious interpretation of the combination of these traits. All these data reinforce the concept of a very early bipedal locomotion in human history, even if at this stage other modes of locomotion were also practiced.

This work was supported by the French Ministry for Europe and Foreign Affairs, the Chadian Government, the French National Research Agency (ANR), the Nouvelle-Aquitaine Region, the CNRS, the University of Poitiers and the French representation in Chad. It is dedicated to the memory of the late Yves Coppens, precursor and inspirer of the MPFT’s work in the Djourab Desert.

1 At the PALEVOPRIM laboratory (CNRS / University of Poitiers).

2 See these two articles:

A new hominid from the Upper Miocene of Chad, Central Africa, Michel Brunet et al., Nature, 11 July 2002. DOI: 10.1038/nature00879.

Virtual cranial reconstruction of Sahelanthropus tchadensis, Christoph P.E. Zollikofer et al., Nature, 7 April 2005. DOI: 10.1038/nature03397

If our reporting has informed or inspired you, please consider making a donation. Every contribution, no matter the size, empowers us to continue delivering accurate, engaging, and trustworthy science and medical news. Independent journalism requires time, effort, and resources—your support ensures we can keep uncovering the stories that matter most to you.

Join us in making knowledge accessible and impactful. Thank you for standing with us!