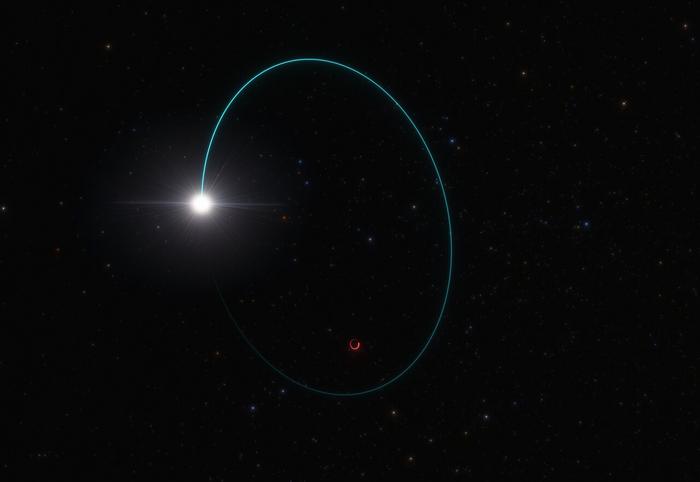

Astronomers have found the most massive stellar black hole ever discovered in our Milky Way galaxy. This black hole, named Gaia BH3 or simply BH3, was spotted in data from the European Space Agency’s Gaia mission due to the strange “wobbling” motion it causes in its companion star. The black hole’s mass was confirmed using data from the European Southern Observatory’s Very Large Telescope (ESO’s VLT) and other ground-based observatories, revealing that it is an impressive 33 times the mass of the Sun.

Stellar black holes form when massive stars collapse, and the ones previously found in the Milky Way have an average mass of about 10 times that of the Sun. Even the next most massive stellar black hole known in our galaxy, Cygnus X-1, only reaches 21 solar masses, making this new discovery truly exceptional.

A Nearby Cosmic Monster

Remarkably, BH3 is not only massive but also extremely close to us, located a mere 2000 light-years away in the constellation Aquila. It is the second-closest known black hole to Earth. The discovery was made while astronomers were reviewing Gaia observations in preparation for an upcoming data release. Pasquale Panuzzo, an astronomer at the Observatoire de Paris and a member of the Gaia collaboration, expressed his surprise, stating, “No one was expecting to find a high-mass black hole lurking nearby, undetected so far. This is the kind of discovery you make once in your research life.”

To confirm their findings, the Gaia collaboration used data from ground-based observatories, including the Ultraviolet and Visual Echelle Spectrograph (UVES) instrument on ESO’s VLT in Chile. These observations revealed key properties of the companion star, which, combined with Gaia data, allowed astronomers to precisely measure the mass of BH3.

A Missing Link in Black Hole Formation

Astronomers have previously found similarly massive black holes outside our galaxy using different detection methods. They have theorized that these black holes may form from the collapse of stars with very few elements heavier than hydrogen and helium in their chemical composition. These “metal-poor” stars are thought to lose less mass over their lifetimes, leaving more material to produce high-mass black holes after their death. However, evidence directly linking metal-poor stars to high-mass black holes has been lacking until now.

UVES data showed that BH3’s companion star is very metal-poor, indicating that the star that collapsed to form BH3 was also metal-poor, just as predicted. This discovery provides a missing link in our understanding of how high-mass black holes form.

The research study, led by Panuzzo, is published today in Astronomy & Astrophysics. Co-author Elisabetta Caffau, also a member of the Gaia collaboration from the CNRS Observatoire de Paris, explained, “We took the exceptional step of publishing this paper based on preliminary data ahead of the forthcoming Gaia release because of the unique nature of the discovery.” By making the data available early, other astronomers can begin studying this black hole immediately, without waiting for the full data release planned for late 2025 at the earliest.

Further observations of this system could reveal more about its history and the black hole itself. The GRAVITY instrument on ESO’s VLT Interferometer, for example, could help astronomers determine if the black hole is pulling in matter from its surroundings and better understand this exciting object.

If our reporting has informed or inspired you, please consider making a donation. Every contribution, no matter the size, empowers us to continue delivering accurate, engaging, and trustworthy science and medical news. Independent journalism requires time, effort, and resources—your support ensures we can keep uncovering the stories that matter most to you.

Join us in making knowledge accessible and impactful. Thank you for standing with us!