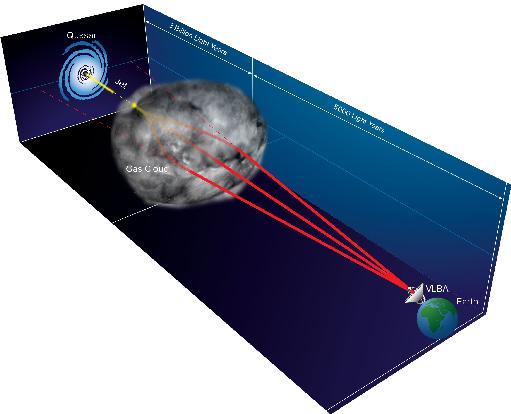

For the first time, astronomers have seen the image of a distant quasar split into multiple images by the effects of a cloud of ionized gas in our own Milky Way Galaxy. Such events were predicted as early as 1970, but the first evidence for one now has come from the National Science Foundation’s Very Long Baseline Array (VLBA) radio telescope system.

The scientists observed the quasar 2023+335, nearly 3 billion light-years from Earth, as part of a long-term study of ongoing changes in some 300 quasars. When they examined a series of images of 2023+335, they noted dramatic differences. The differences, they said, are caused by the radio waves from the quasar being bent as they pass through the Milky Way gas cloud, which moved through our line of sight to the quasar.

“This event, obviously rare, gives us a new way to learn some of the properties of the turbulent gas that makes up a significant part of our Galaxy,” said Matt Lister, of Purdue University.

The scientists added 2023+335 to their list of observing targets in 2008. Their targets are quasars and other galaxies with supermassive black holes at their cores. The gravitational energy of the black holes powers “jets” of material propelled to nearly the speed of light. The quasar 2023+335 initially showed a typical structure for such an object, with a bright core and a jet. In 2009, however, the object’s appearance changed significantly, showing what looked like a line of bright, new radio-emitting spots.

“We’ve never seen this type of behavior before, either among the hundreds of quasars in our own observing program or among those observed in other studies,” Lister said.

The multiple-imaging event came as other telescopes detected variations in the radio brightness of the quasar, caused, the astronomers said, by scattering of the waves.

The scientists’ analysis indicates that the quasar’s radio waves were bent by a turbulent cloud of charged gas nearly 5,000 light-years from Earth in the direction of the constellation Cygnus. The cloud’s size is roughly comparable to the distance between the Sun and Mercury, and the cloud is moving through space at about 56 kilometers per second.

Monitoring of 2023+335 over time may yield more such events, the scientists said, allowing them to learn additional details both about the process by which the waves are scattered and about the gas that does the scattering. Other quasars that are seen through similar regions of the Milky Way also may show this behavior.

The monitoring program that yielded this discovery is called MOJAVE (Monitoring Of Jets in Active galactic nuclei with VLBA Experiments), run by an international team of scientists led by Lister. The analysis of this rare event was spearheaded by Alexander Pushkarev of the Max Planck Institute for Radioastronomy in Germany. The researchers recently published their results in the journal Astronomy and Astrophysics.

The National Radio Astronomy Observatory is a facility of the National Science Foundation, operated under cooperative agreement by Associated Universities, Inc.

If our reporting has informed or inspired you, please consider making a donation. Every contribution, no matter the size, empowers us to continue delivering accurate, engaging, and trustworthy science and medical news. Independent journalism requires time, effort, and resources—your support ensures we can keep uncovering the stories that matter most to you.

Join us in making knowledge accessible and impactful. Thank you for standing with us!