Republican nominee Mitt Romney didn’t lose the 2012 presidential election because he was too conservative. His infamous remark about not feeling responsible for 47 percent of voters didn’t cost him the White House either. He wasn’t even particularly hobbled by choosing Paul Ryan as his running mate.

Conventional wisdom doesn’t hold for President Barack Obama’s victory either. He didn’t win the election, as his opponent claimed, in return for “gifts” to constituencies, like health care reform or the temporary liberalization of immigration policies for Mexican nationals who moved to this country as minors. Neither was he returned to office by his much-lauded ground game, a post-racial electorate or an advertising strategy that emphasized front-loading. And Hurricane Sandy had nothing to do with it.

In fact, most of what you think you know about the 2012 presidential race is wrong, suggests a forthcoming book by political scientists at UCLA and George Washington University.

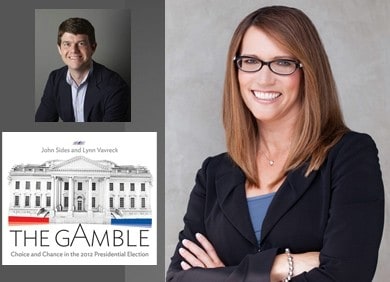

In “The Gamble: Choice and Chance in the 2012 Presidential Election,” which Princeton University Press will publish Oct. 2, Lynn Vavreck, a UCLA associate professor of political science, and John Sides, a GWU associate professor of political science, argue that the race was influenced more by the economy than any of the above factors.

“The ‘gift’ that made the most difference for Obama’s fortunes on Election Day was the slowly growing economy, and that was a gift to everyone — not just his supporters,” Vavreck said.

Unlike Silver or Wagner, however, Vavreck and Sides also partnered with the market research firm YouGov Inc. to survey voters, returning over and over again to a representative sample of 45,000 Americans, which allowed them to paint a dynamic picture of forces that affected — or didn’t affect — the election’s outcome.

In their analysis, they also factored in historical trends, media coverage of the election and political advertisements that appeared in 210 media markets. The result is the first academic book to look at the 2012 election, and it’s hitting the market at the same time as journalistic accounts of the event. But where other books spell out why the two campaigns did what they did, “The Gamble” sets out to demonstrate whether what the campaigns did made any difference in the election’s outcome.

Historically, the rate of growth of the economy leading up to Election Day is the single most important factor in determining a U.S. presidential race, Vavreck’s own research has shown. A first-term incumbent needs only a moderately growing economy to return to the White House, provided he takes credit for the economic gains, she has found.

Forecasting an annualized growth rate of 1.7 percent in the six months before the 2012 election, Vavreck and Sides predicted in December 2011 that Obama would win the election with 52.9 percent of the popular vote. He ended up winning with 52 percent, while Romney garnered 47 percent.

Among other findings:

- In a race where each candidate spent about a billion dollars, their respective advertising blitzes largely neutralized each other. Moreover, any boost in support from advertising decayed within five days. Most of the effects of ads were gone within a day.

- Despite the perception that the Republican primary cost Romney the election by forcing him to run a much more conservative campaign than he might otherwise have done, Romney was actually perceived to be closer ideologically to the average voter than Obama. “Obama appeared to be the candidate more ideologically out of step with American voters in 2012,” Vavreck and Sides write.

- Racial prejudice was a factor in 2012 and may have cost Obama 3 percent of the vote, calling into question the “post-racial America” that his 2008 victory heralded for some pundits. On the other hand, incumbency typically boosts support by 3 percentage points.

- Despite being the focus of intense media attention, such political gaffes as Obama’s insistence that the private sector was “doing fine” while the nation was still in the shadow of the 2007–08 recession and Romney’s comment that 47 percent of Americans can’t be persuaded to take personal responsibility had only a small and temporary effect on persuadable voters’ attitudes about the candidates and resulted in very little shift in voters’ intentions.

- Even though Romney chalked Obama’s victory up to “gifts” to certain constituencies, such as the Affordable Care Act and Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals, Obama’s support of these policies had very little effect.

- While polls showed that more voters had a negative view of Ryan than had a positive view, his selection did not affect the election’s outcome. In fact, vice-presidential picks have had at most a small influence on modern presidential elections, history has shown.

- The public perception of the Obama administration’s response to Hurricane Sandy neither halted Romney’s momentum nor caused a clear shift to Obama.

Despite the fact that the election’s outcome was predictable close to a year in advance, Vavreck and Sides stop short of contending that it was preordained. They maintain that the two rivals were so equally matched that the election constituted a kind of tug of war.

“The flag in the middle of the rope remains stationary if both sides pull with equal force, which is what occurred in this election,” Vavreck said. “If one side decided to stop pulling or discovered a better strategy for pulling, you would have seen the flag fly, but that didn’t happen.”

In this way, each campaign served to balance the other campaign’s efforts. Like all elections, the 2012 campaign also served to encourage “voters to join the fold to which they belong,” Sides said. “What a campaign does is activate the political dispositions of voters.”

That dynamic was especially important for undecided voters, Vavreck and Sides found. For most of the election, polls showed that 6 percent of voters were undecided — a spread large enough to determine the election. Yet the numbers actually obscured two key characteristics of the group, Vavreck and Sides determined with their surveys. First, despite describing themselves as undecided, many of these voters actually harbored partisan loyalties, and they ultimately voted accordingly. Second, it was not the same 6 percent of voters who declared themselves “undecided” throughout the entire election. From week to week, voters shifted in and out of the ranks of the undecided as the candidate they most identified with appealed to or disappointed them.

The most vivid example of the trend, Vavreck and Sides write, occurred after Romney’s “47 percent” comment. In the following two weeks, some supporters left his camp, but instead of throwing support behind Obama, they identified themselves as “undecided.” When Romney nailed the first presidential debate two weeks later, these partisans returned to him as supporters, accounting for a strong surge in his direction in the polls.

If our reporting has informed or inspired you, please consider making a donation. Every contribution, no matter the size, empowers us to continue delivering accurate, engaging, and trustworthy science and medical news. Independent journalism requires time, effort, and resources—your support ensures we can keep uncovering the stories that matter most to you.

Join us in making knowledge accessible and impactful. Thank you for standing with us!