A key question central bankers would like to answer is how people form expectations about future inflation. It’s an important input, since the public’s expectations of inflation can become self-fulfilling.

New research from U-M Ross finance professor Stefan Nagel has shed some light on how people develop that expectation. It turns out to be deeply influenced by their personal experience with inflation.

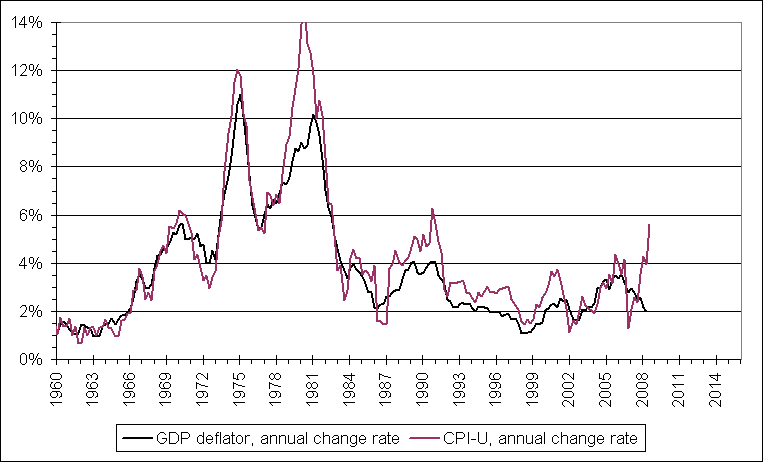

His study shows that people tend to give more weight to inflation realized during their lifetimes when trying to predict the future. A young person who hasn’t experienced high inflation has different expectations of future inflation than somebody who lived through the high inflation of the 1970s.

This experience with inflation also affects their personal finance decisions, such as what types of mortgages to choose. The research is explained in the paper, “Learning from Inflation Experiences.”

“Ideally, someone in Ben Bernanke’s position would like to say they will keep inflation at 2 percent, and everyone would believe it. That would make their job very easy,” says Nagel, who recently joined the Ross faculty from Stanford. “But in the real world, it’s more complicated. If expectations are shaped by experiences, the public needs to experience low and stable inflation for a while before it actually believes in it.”

Nagel and co-author Ulrike Malmendier of the University of California-Berkeley studied 57 years of data on inflation expectations from the Thomson Reuters/University of Michigan Survey of Consumers, tracking quarterly numbers and age cohorts. They found that differences in lifetime experiences strongly predict differences in inflation expectations.

Learning from experience explains the wide disparity between old and young in periods of high inflation, like the 1970s, since people update their beliefs as they age. Younger people are more influenced by recent events while older folks have more data to form their expectations.

Younger people in the 1970 and 1980s forecast much higher inflation than older people because they had experienced high inflation for a larger portion of their lives. It’s the same reason younger people today expect little inflation — rates have been low for several years.

Nagel’s research also found that these inflation expectations affect individual financial decisions. Households that expect higher inflation, according to the learning-from-experience model, are more inclined than others to use fixed-rate mortgages rather than variable rate.

“This is a new way of looking at inflation expectations,” says Nagel, also professor of economics at U-M. “Modeling using these experience effects hasn’t been done. But we have enough data now and we can show that experience strongly influences not only expectations on inflation, but also personal economic decisions.”

If our reporting has informed or inspired you, please consider making a donation. Every contribution, no matter the size, empowers us to continue delivering accurate, engaging, and trustworthy science and medical news. Independent journalism requires time, effort, and resources—your support ensures we can keep uncovering the stories that matter most to you.

Join us in making knowledge accessible and impactful. Thank you for standing with us!