Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, better known as Lou Gehrig’s disease, is a devastating illness that gradually robs sufferers of muscle strength and eventually causes a lethal, full-body paralysis. The only drug available to treat the disease extends life spans by a meager three months on average.

In a new study published in Nature Genetics, University of Pennsylvania researchers and colleagues have made inroads into the mechanism by which ALS acts. Working with a powerful fruit fly model of the disease, they found a way of reducing disease toxicity that slows the dysfunction of neurons and showing that a parallel mechanism can reduce toxicity in mammalian cells. Their discoveries offer the possibility of a new strategy for treating ALS.

The senior author of the study is Nancy M. Bonini, a professor in the Department of Biology in Penn’s School of Arts and Sciences. Contributors from her lab include Hyung-Jun Kim, Leeanne McGurk and Ross Weber. They partnered on the work with long-time collaborators from Penn’s Perelman School of Medicine, John Q. Trojanowski and Virginia M-Y Lee. Additional co-authors included Alya R. Raphael and Aaron D. Gitler of Stanford University and Eva S. LaDow and Steven Finkbeiner of the Gladstone Institute of Neurological Disease.

Recent years have seen an uptick in scientific understanding of the genetic roots of ALS.

“There’s been an explosion over the last five-plus years in the identification of genes that contribute to genetically inherited ALS,” Bonini said.

One of the key genes that has come to light as playing a role in the disease is called TDP-43, which binds to RNA and has been found to aggregate abnormally in the cytoplasm of patients with ALS.

Previous studies led by Gitler and Bonini, working with colleagues including Trojanowski and Lee, had found that TDP-43 interacts with a gene called ataxin-2.

“That became very interesting to us because ataxin-2 on its own is a gene whose mutations cause human degenerative disease,” Bonini said.

Given the strong interactions between TDP-43 and ataxin-2, and additional findings of an association of ataxin-2 with ALS, the team continued investigating this interaction. Bonini’s lab has long pursued questions about neurodegenerative disease using the fruit fly as an animal model and did so again in this work.

“These model systems are very fast and simpler than mammalian models,” Bonini said. “They allow us to focus on conserved pathways and can be remarkably powerful for giving us insight into pathways involved in disease.”

Using yeast models and the fly, the team showed that genes that modulate cellular structures known as stress granules, which act as holding pens for RNA and proteins when cells are under stress, modify TDP-43 toxicity. Previous work had suggested that ALS patients may have abnormal accumulations of stress granule components, indicating that the structures might somehow be tied to the disease. In flies, the Bonini team found that expression of genes predicted to promote stress granules increased the toxic activity of TDP-43 in genetic screens, underlining the importance of these structures to the pathology of ALS.

Investigating fruit flies engineered to express the human version of TDP-43, they found the flies showed signs of a build-up of stress granule components, as evidenced by an increase in the tagging of a molecule called eIF2α with a phosphate group. eIF2α phosphorylation is associated with formation of stress granules and reduced generation, or translation, of proteins. These flies also had symptoms reflective of ALS; they could not climb as readily as normal flies and had shorter lifespans.

The researchers were able to modulate these symptoms, however, by altering the expression of genes related to eIF2α phosphorylation and stress granules.

Further, using transgenic flies, the team identified a region of the ataxin-2 protein critical for increasing the detrimental effects of TDP-43. That region is known to be a binding site of a protein called poly-A binding protein, or PABP, that is also known to go to stress granules.

“If you knock out that domain, there is a dramatically reduced interaction between TDP-43 and ataxin-2,” Bonini said. “That, coupled with our other data, is suggestive of the idea that the disease state may be associated with pathological stress granules. Perhaps they are remaining in the cell too long or not being resolved properly.”

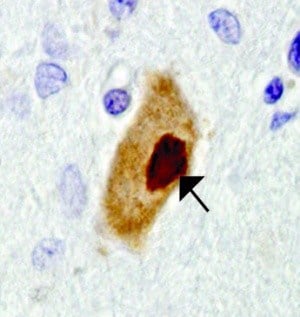

As in the flies, PABP may factor into human disease, the researchers found. Examining ALS patients’ spinal cord tissue, they found dense aggregations of PABP in the cytoplasm, reminiscent of stress granules.

Finally, the researchers went back to the fly to see if they could reverse the TDP-43 toxicity.

They fed flies a compound developed by GlaxoSmithKline that inhibits the addition of phosphate groups to eIF2α. Reducing eIF2α phosphorylation is predicted to mitigate stress granule formation and the state of translational repression associated with stress granules. Upon feeding flies, they witnessed a dramatic restoration of physical strength in the flies expressing TDP-43. Those fed the compound retained more climbing ability compared with animals without the compound.

To test the effectiveness of the GSK compound in mammalian cells, the team exposed rat neuron cells expressing TD-43 in culture to the compound, and found it reduced the risk of cell death. The data raise the possibility that the prolonged stress state associated with stress granules and the deleterious effects on cellular pathways associated with such prolonged stress are important in disease.

Bonini suggests the results show promise for a treatment strategy for ALS and highlight again the power that flies, yeast and other seemingly simple model organisms can have in shedding light on human neurological disease.

Bonini suggests the results show promise for a treatment strategy for ALS and highlight again the power that flies, yeast and other seemingly simple model organisms can have in shedding light on human neurological disease.

“We can integrate from a number of extraordinarily powerful systems, including yeast, fly and then mammalian cell culture, to see if, with this united front, can we provide evidence from all spokes that the approach is suggestive of a therapeutic effect,” she said. “They are all important pieces of the puzzle.”

The study was funded by the National Institutes of Health, the Howard Hughes Medical Institute, the Robert Packard Center for ALS, the Williams H. Adams Foundation, Target ALS and a BrightFocus Alzheimer’s disease grant.

If our reporting has informed or inspired you, please consider making a donation. Every contribution, no matter the size, empowers us to continue delivering accurate, engaging, and trustworthy science and medical news. Independent journalism requires time, effort, and resources—your support ensures we can keep uncovering the stories that matter most to you.

Join us in making knowledge accessible and impactful. Thank you for standing with us!