In the future, when an earthquake or tsunami strikes a populated area or a terrorist attack decimates a city, teams of disaster experts partnered with robots — whose skills are being honed in rigorous competitions funded by the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency — may be the first responders.

Launched in October 2012, the DARPA Robotics Challenge has held two of three competitions -– a virtual event in June 2013 and a live two-day event held Dec. 20-21 at the Homestead-Miami Speedway in Florida.

The first competition tested software teams’ ability to guide a simulated robot through three sample tasks in a virtual environment. In December, teams had to guide their robots through as many as eight individual physical tasks that tested robot mobility, manipulation, dexterity, perception and operator-control mechanisms.

During the finals, to be held sometime in the next 12-18 months, human-robot teams will attempt a circuit of consecutive physical tasks with degraded communications between the robots and their operators. The winning team will receive a $2 million prize.

“Over a period of less than three years,” program manager Dr. Gill Pratt wrote in the January-February edition of The Bulletin of Atomic Scientists, “DARPA expects the field of robotics to undergo a historic transformation that could drive innovation in robots for defense, health care, agriculture and industry.”

Pratt has a doctorate in electrical engineering and computer science from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and is a professor at the Franklin W. Olin College of Engineering in Needham, Mass. He’s also the DARPA Robotics Challenge program manager in DARPA’s Defense Sciences Office.

Having people and robots work together in teams is essential to robot success in disaster response, Pratt told American Forces Press Service during a recent interview at DARPA headquarters in Arlington, Va.

“For the foreseeable future, our robots are not going to have anywhere near the intelligence they require to do even small parts of missions on their own,” he said. “They’re going to require a human being to figure out what the plan is, to figure out what the contingencies are [and] to understand the situation.”

What robots can do, Pratt explained, is contribute sensing and physical effects at a distance from a human controller, operating in a dangerous environment while a human operator stays back where it’s safe and directs the action.

“Together, working as a team,” he added, “they can be more effective than either one of them working by themselves.”

DARPA officials know this from their own experiences.

In the days after 9/11, DARPA sent to New York City robots whose development the agency had funded. But those robots found no survivors, Pratt recalled in an analytic piece published Dec. 3 in The Bulletin of Atomic Scientists.

DARPA tried again in March 2011 in the deadly aftermath of a magnitude 9.0 earthquake centered 81 miles off the coast of the city of Sendai on the eastern coast of Honshu Island, Japan.

A subsequent 49-foot tsunami killed more than 19,000 people, destroyed or damaged more than a million buildings and shut down power in and flooded Tokyo Electric Power Co.’s Fukushima Daiichi nuclear plant, melting the reactor cores of operating units 1, 2 and 3, and damaging unit 4.

Japanese officials declared a nuclear emergency later that day and evacuated people initially within 1.2 miles of the plant and later within 12 miles.

Humanitarian assistance and disaster relief is a primary DOD mission, Pratt wrote in the Dec. 3 Bulletin, and as the disaster unfolded in Japan

“DARPA officials contacted researchers who had designed robots for the Three Mile Island and Chernobyl disasters and coordinated with companies that DARPA had funded to develop other robots.”

Each company already was making plans to send its robots and training personnel to Japan, he added, and others around the world sent robots as well, but it took weeks for power-plant personnel to complete training they needed to operate the robots.

By then, Pratt said, “the golden hours for early intervention to mitigate the extent of the disaster had long since passed.”

Even with progress made in the DARPA Robotics Challenge and elsewhere in the industry, Pratt said, “We don’t know how to make [robots] intelligent enough to do sophisticated tasks, [but] we do know how to make them do … very specific subtasks.”

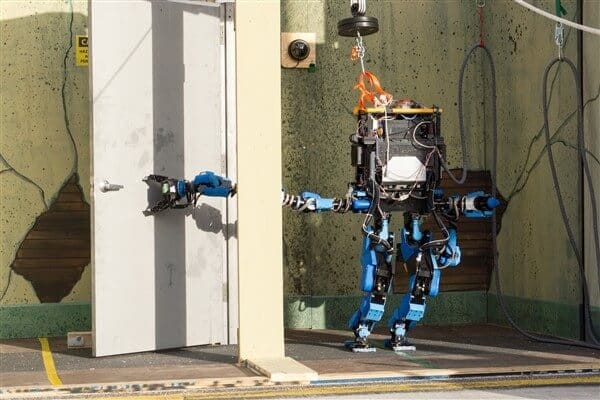

These days in a laboratory, he explained, a robot can be told to open a door and the robot will use its visual sensors to locate the door, compare that image against a library of different handles it’s been programmed to recognize, turn the door handle and pull the door open.

“At the DARPA Robotics Challenge, we were trying to be successful with that out in the field, where lighting conditions are varied, where the location you’re looking at the door from changes all the time, there are shadows, there are other things in front of the door,” Pratt said. “We were trying to make it robust to all those changes, and that’s really where the state of the art is now.”

Most of the challenge tasks were on a slope that started out easy and went to medium and then hard, he said. The challenge began with 16 robot teams and ended with eight robot teams qualifying to receive DARPA funding for the finals event.

Pratt said most differences seen in the robots’ performances were differences of software capabilities. But it wasn’t that the robot hardware was more capable in some cases, he said, adding that most of the robots were quite good at the tasks “and, in fact, did better than we had expected them to.” The software differentiation was mostly in how well the teams handled the communications degradation inserted into the challenge, Pratt said.

“Some teams did very well and [their] robot had enough subtask autonomy that it was able to do some meaningful work while communications was poor. Other teams … could only really control the robot well when the communications quality was higher,” he explained.

“The key to robustness is feedback, and the key to feedback in a robot is the ability to perceive the environment well,” Pratt said.

Looking toward the DARPA Robot Challenge finals, Pratt said, officials learned in the December trials that the robots were about 20 percent more capable mechanically than expected, so they will raise the bar accordingly for the finals.

The plan is to make the tasks more difficult and more authentic than they were in the trials, he said.

“My thought right now, and this is subject to change,” Pratt added, “is [to] take the eight different tasks we had as separate events in the trials and … combine them into an integrated task where the robot has to respond to a situation,” chaining together capabilities it demonstrated in the trials.

Finals officials will tell the teams much less than they were told before the trials so the setup will be a surprise to all entrants. And Pratt said they’re planning to degrade communications more than they did during the trials.

“We’re going to have the comms go black and dead for significant lengths of time and … see whether the robots can continue to execute some of these subtasks on their own … because we know those kinds of dropouts are quite common in the austere environments we care about,” he said.

Also in the finals, the robots won’t use safety harnesses as they did in the December trials.

“If the robot falls down, it must first not be damaged so badly that it can’t continue to work,” Pratt said. “But even more difficult, it needs to be able to get itself back up, even if it falls down on rough terrain. We think those behaviors are absolutely essential for true work in austere environments.”

DARPA officials aren’t sure yet what the finals scenario will include, but it will focus more on disaster response than on trying to save injured people.

“Trying to affect the properties so the disaster doesn’t get worse is part one, trying to save human beings who are hurt or even recover them if they were killed is part two, and part three is how to remediate the disaster and make the site good again for use,” he said. “The DARPA Robotics Challenge is really focused on the first one.”

Pratt said DARPA expects roughly a dozen teams to participate in the finals, including the top eight teams from the December trials that are in contract negotiations with DARPA to receive $1 million for development this year, and other teams from around the world that will fund their own software development.

After the finals, when the winner walks away with $2 million, the technology still won’t be quite ready for commercialization.

“The technology will be ready for commercialization if a market can be found in the commercial world for it,” Pratt said. “What many people don’t realize is that the defense market is a very small fraction of the size of the commercial market.”

He added, “After we show the feasibility of things, after we provide the spark to start it, then we need to enter a phase where the costs get driven down. And the commercial world typically is very, very good for that.”

If our reporting has informed or inspired you, please consider making a donation. Every contribution, no matter the size, empowers us to continue delivering accurate, engaging, and trustworthy science and medical news. Independent journalism requires time, effort, and resources—your support ensures we can keep uncovering the stories that matter most to you.

Join us in making knowledge accessible and impactful. Thank you for standing with us!