A team of neuroscientists has reversed psychosis-like features in mice, raising hope that scientists may ultimately be able to do the same for humans with schizophrenia – and potentially other kinds of psychiatric disorders.

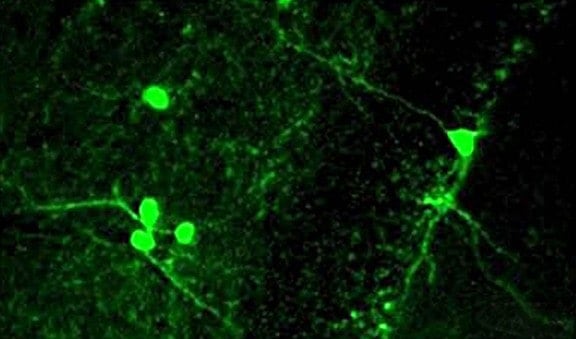

The study, reported online in the May 2 issue of PNAS, demonstrated that a transplant of a small population of “interneurons” into the brains of affected mice normalized mental processing. About one-third of a particular type of interneurons, which help brain cells communicate with each other, are missing in these mice. Other studies in humans indicate that interneurons are also lost or are not functioning properly in patients with a variety of behavioral disorders, ranging from schizophrenia to autism spectrum.

“Loss of interneurons has a profound effect on overall brain activity. Disorders in the autism spectrum, seizure disorders, disorders such as schizophrenia and certain types of major depression that include psychosis as one of their features are believed to originate, in part, from reduced interneuron function,” says the study’s co-lead investigator, Dr. M. Elizabeth Ross, the Nathan Cummings Professor of Neurology and Neuroscience at the Feil Family Brain and Mind Research Institute at Weill Cornell Medical College.

“What excites us is that some of the major features of schizophrenia that are displayed by these mice can be reversed in adulthood, even after onset of symptoms, by adding a small number of cells in a very defined region of the brain’s hippocampus,” Dr. Ross says, referring to a region of the brain responsible for memory and certain types of behavior. “That provides the prospect that cell therapy could bring schizophrenia, and potentially other disorders related to faulty interneurons, under much better control by restoring the neuronal balance in critical brain regions.”

While perfecting neuronal transplantation directly into human brains will take time, drug therapy that boosts the function of remaining interneurons and reverses symptoms of schizophrenia “could be advanced more rapidly,” she says.

Dr. Ross is one of three principal investigators in the study, now in its eighth year. The other lead authors are from the New York State Psychiatric Institute-Columbia University and the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia.

The work is based on a finding by Dr. Ross and her colleagues that mice born without the gene that produces a protein crucial to regulating brain size and organization are missing between 30 and 40 percent of interneurons needed for normal brain architecture.

She says that mice that are deficient in the protein, cyclin D2, “lack a kind of rheostat or dimmer-switch control of neuronal activity. Activity in the brain is not appropriately regulated, leading to increased risk of seizures and psychosis-related behaviors in these mice.”

The researchers found that these behavioral abnormalities are caused, in part, by hyperactive neurons in the hippocampus; faulty communication between neurons long believed to be linked to schizophrenia; and increased metabolic activity in the hippocampus.

“The fact that interneuron cell transplantation can reverse these important features in adult animals provides proof of principle that therapies targeting interneurons — either with drugs that enhance interneuron function or provision of cells to supplement their numbers — may be effective treatments in adults suffering from schizophrenia even once symptoms have occurred,” Dr. Ross says.

If our reporting has informed or inspired you, please consider making a donation. Every contribution, no matter the size, empowers us to continue delivering accurate, engaging, and trustworthy science and medical news. Independent journalism requires time, effort, and resources—your support ensures we can keep uncovering the stories that matter most to you.

Join us in making knowledge accessible and impactful. Thank you for standing with us!