It seems that research into Antarctic penguins and viruses has gone, well, viral.

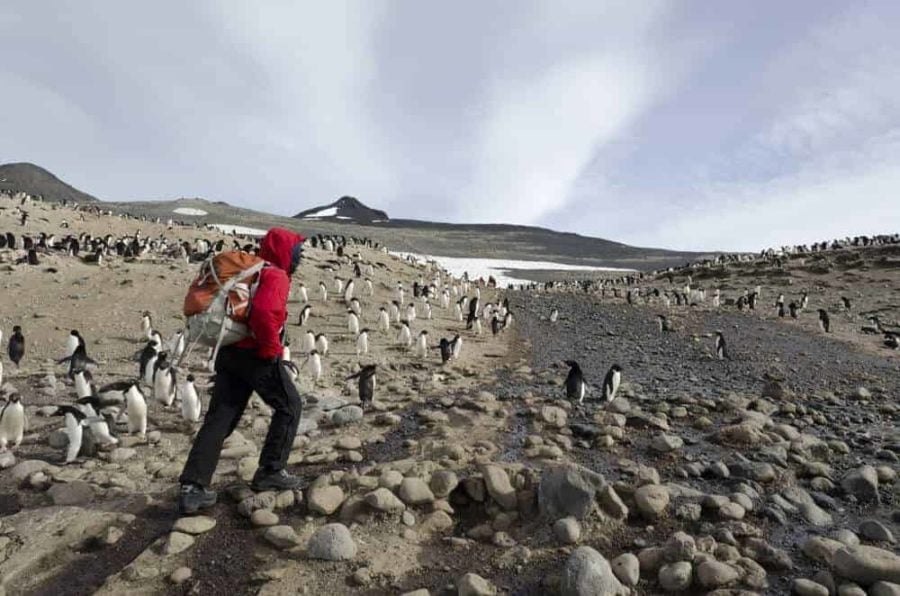

A team of researchers funded by the National Science Foundation has reported finding a novel papillomavirus among the Adélie penguins on Ross Island, joining another group led by Australian scientists who also recently announced they found a new strain of avian flu amongst a population of Adélie penguins around the Antarctic Peninsula.

The former finding, published in the Journal of General Virology earlier this year, is the first report of a papillomavirus associated with a penguin species. Only three papillomaviruses have previously been identified in birds, though there are hundreds of types, including many that infect humans.

“I was not expecting to find an avian papillomavirus to be honest,” said lead author Arvind Varsani , an expert in virology at the University of Canterbury in New Zealand. Varsani has worked two seasons in Antarctica on a long-term project studying the population dynamics of Adélie penguins in the Ross Sea region. [See recent article — Power of one: Individual differences count in one of the world’s largest Adélie penguin colonies.]

“I thought what we’d find would be novel viruses that are highly divergent from any known viruses,” he explained via e-mail. “The Antarctic ecosystem is quite unique, and hence I imagined that the viruses found there would probably require the establishment of new viral families to accommodate these viruses.”

Papillomaviruses (PV) typically infect the skin or mucus membranes in most vertebrate species. Human PV types can cause benign warts, though types that are more serious can become cancerous.

Varsani said the scientists have no idea if the Adélie papillomavirus is benign or not.

“To be honest, I’d say we [know] extremely little about viruses associated with penguins,” Varsani said.

The handful of previous studies on viruses associated with penguin species relied on serology, using blood samples to identify the specific antibodies associated with certain types of viruses. The current studies rely on genetic techniques. In the research led by Varsani, the team used a noninvasive technique, collecting fecal matter, and then extracted the total viral DNA, followed by DNA sequencing and database searches to determine the entire genome of the virus.

Varsani said there are several important reasons for studying viruses in penguins, not least of which is to establish a baseline on virology in Antarctica, which is the least studied of the continents in this field. Research will also allow scientists to identify emerging viruses, especially those that may appear as the climate changes.

“Viruses are everywhere and infect organisms in every domain of life,” Varsani said. “With habitat loss we are bound to see a higher incidence of emerging viruses that will spill over from well-established ecosystems to ‘altered’ ecosystems.”

Varsani is also collaborating with other U.S. Antarctic Program researchers working on permafrost melt in the McMurdo Dry Valleys and the potential for discovering new viruses locked in the ice since the last glacial period.

“This opens up some important questions about pathogens in the Antarctic, including flow of pathogens from sled dogs to seals,” Varsani said, referring to a real concern that led to the eventual banishment of canines from Antarctica in 1994, “or as a matter of fact from any organism to another. [It] also raises a serious question with climate change: are the current ecosystems being seeded with pathogens trapped in the last glacial ice age?”

During the 2011-12 season, before Varsani joined the team, researchers had noted a high incidence of what looked like “beak-and-feather” disease, according to David Ainley, principal investigator on the long-term population dynamics study in the Ross Sea region.

The suspected virus, which is known to affect parrots, caused the loss of feathers mainly around the birds’ faces and bills across about 10 percent of the penguins. The next year, it was mostly gone, said Ainley, senior ecologist at a San Francisco Bay Area ecological consulting firm, H.T. Harvey and Associates.

Tests on blood samples collected from the birds for other studies related to the individual fitness and breeding success of some Adélies over others were inconclusive.

“There has been evidence of very low presence of whatever it was since,” Ainley added, saying less than 1 percent of the population still seems to be affected.

In the study that discovered avian influenza among the Adélie penguins of the Antarctic Peninsula – published in mBio, the online open-access journal of the American Society for Microbiology External Non-U.S. government site – researchers echoed the same concerns voiced by Varsani.

“We found that this virus was unlike anything else detected in the world,” said lead author Aeron Hurt External Non-U.S. government site, a senior research scientist at the World Health Organization Collaborating Centre for Reference and Research on Influenza External Non-U.S. government site in Melbourne, Australia, in a press release External Non-U.S. government site.

Like the rapidly evolving viruses themselves, the study of virology in the Antarctic appears to be evolving rapidly. A preprint version of a paper in the journal Infection, Genetics and Evolution by Peyman Zawar-Reza et al, a study led by Varsani, reported identifying eight novel viruses from algal mats found in a freshwater pond on the McMurdo Ice Shelf sampled in 1988 by Paul Broady External Non-U.S. government site at the University of Canterbury.

Varsani said more papers are forthcoming on other novel viruses discovered among the penguin populations and melting permafrost in the Dry Valleys.

“We are living in a rapidly changing environment, as a result of climate change and human activities (some of our negative impacts on ecosystems including deforestation, over fishing, pollution, etc.),” Varsani said. “These have huge implications on pathogen evolution and spread.”

If our reporting has informed or inspired you, please consider making a donation. Every contribution, no matter the size, empowers us to continue delivering accurate, engaging, and trustworthy science and medical news. Independent journalism requires time, effort, and resources—your support ensures we can keep uncovering the stories that matter most to you.

Join us in making knowledge accessible and impactful. Thank you for standing with us!