One of the great mysteries of anesthesia is how patients can be temporarily rendered completely unresponsive during surgery and then wake up again, with their memories and skills intact.

A new study by Dr. Andrew Hudson, an assistant professor in anesthesiology at the David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA, and colleagues provides important clues about the processes used by structurally normal brains to navigate from unconsciousness back to consciousness. Their findings are currently available in the early online edition of the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Previous research has shown that the anesthetized brain is not “silent” under surgical levels of anesthesia but experiences certain patterns of activity, and it spontaneously changes its activity patterns over time, Hudson said.

For the current study, the research team recorded the electrical activity from several brain areas associated with arousal and consciousness in a rodent model that had been given the inhaled anesthetic isoflurane. They then slowly decreased the amount of anesthesia, as is done with patients in the operating room, monitoring how the electrical activity in the brain changed and looking for common activity patterns across all the study subjects.

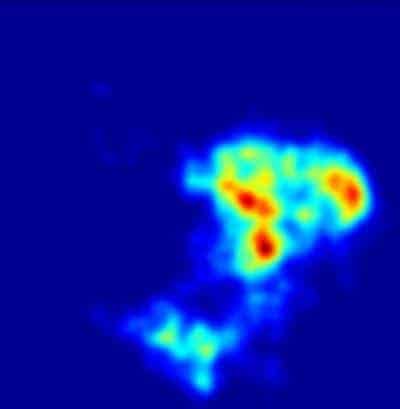

The researchers found that the brain activity occurred in discrete clumps, or clusters, and that the brain did not jump between all of the clusters uniformly.

A small number of activity patterns consistently occurred in the anesthetized rodents, Hudson noted. The patterns depended on how much anesthesia the subject was receiving, and the brain would jump spontaneously from one activity pattern to another. A few activity patterns served as “hubs” on the way back to consciousness, connecting activity patterns consistent with deeper anesthesia to those observed under lighter anesthesia.

“Recovery from anesthesia is not simply the result of the anesthetic ‘wearing off,’ but also of the brain finding its way back through a maze of possible activity states to those that allow conscious experience,” Hudson said. “Put simply, the brain reboots itself.”

The study suggests a new way to think about the human brain under anesthesia, and could encourage physicians to reexamine how they approach monitoring anesthesia in the operating room. Additionally, if the results are applicable to other disorders of consciousness — such as coma or minimally conscious states — doctors may be better able to predict functional recovery from brain injuries by looking at the spontaneously occurring jumps in brain activity.

In addition, this work provides some constraints for theories about how the brain leads to consciousness itself, Hudson said.

Going forward, the UCLA researchers will test other anesthetic agents to determine if they produce similar characteristic brain activity patterns with “hub” states. They also hope to better characterize how the brain jumps between patterns.

If our reporting has informed or inspired you, please consider making a donation. Every contribution, no matter the size, empowers us to continue delivering accurate, engaging, and trustworthy science and medical news. Independent journalism requires time, effort, and resources—your support ensures we can keep uncovering the stories that matter most to you.

Join us in making knowledge accessible and impactful. Thank you for standing with us!