The oxygen-rich surface waters of the world’s major oceans are supersaturated with methane – a powerful greenhouse gas that is roughly 20 times more potent than carbon dioxide – yet little is known about the source of this methane.

Now a new study by researchers at Oregon State University demonstrates the ability of some strains of the oceans’ most abundant organism – SAR11 – to generate methane as a byproduct of breaking down a compound for its phosphorus.

Results of the study are being published this week in Nature Communications. It was funded by the National Science Foundation and the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation.

“Anaerobic methane biogenesis was the only process known to produce methane in the oceans and that requires environments with very low levels of oxygen,” said Angelicque “Angel” White, a researcher in OSU’s College of Earth, Ocean, and Atmospheric Sciences and co-author on the study. “In the vast central gyres of the Pacific and Atlantic oceans, the surface waters have lots of oxygen from mixing with the atmosphere – and yet they also have lots of methane, hence the term ‘marine methane paradox.’

“We’ve now learned that certain strains of SAR11, when starved for phosphorus, turn to a compound known as methylphosphonic acid,” White added. “The organisms produce enzymes that can break this compound apart, freeing up phosphorus that can be used for growth – and leaving methane behind.”

The discovery is an important piece of the puzzle in understanding the Earth’s methane cycle, scientists say. It builds on a series of studies conducted by researchers from several institutions around the world over the past several years.

Previous research has shown that adding methylphosphonic acid, or MPn, to seawater produces methane, though no one knew exactly how. Then a laboratory study led by David Karl of the University of Hawaii and OSU’s White found that an organism called Trichodesmium could break down MPn and thus it could be a potential source of phosphorus, which is a critical mineral essential to every living organism.

However, Trichodesmium are rare in the marine environment and unlikely to be the only source for vast methane deposits in the surface waters.

So White turned to Steve Giovannoni, a distinguished professor of microbiology at OSU, who not only maintains the world’s largest bank of SAR11 strains, but who also discovered and identified SAR11 in 1990. In a series of experiments, White, Giovannoni, and graduate students Paul Carini and Emily Campbell tested the capacity of different SAR11 strains to consume MPn and cleave off methane.

“We found that some did produce a methane byproduct, and some didn’t,” White said. “Just as some humans have a different capacity for breaking down compounds for nutrition than others, so do these organisms. The bottom line is that this shows phosphate-starved bacterioplankton have the capability of producing methane and doing so in oxygen-rich waters.”

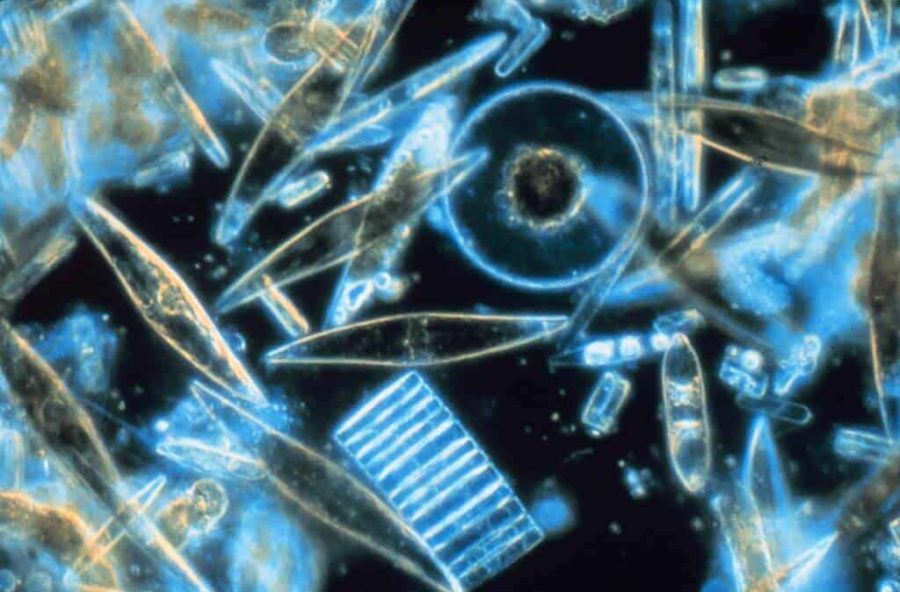

SAR11 is the smallest free-living cell known and also has the smallest genome, or genetic structure, of any independent cell. Yet it dominates life in the oceans, thrives where most other cells would die, and plays a huge role in the cycling of carbon on Earth.

These bacteria are so dominant that their combined weight exceeds that of all the fish in the world’s oceans, scientists say. In a marine environment that’s low in nutrients and other resources, they are able to survive and replicate in extraordinary numbers – a milliliter of seawater, for instance, might contain 500,000 of these cells.

“The ocean is a competitive environment and these bacteria apparently won the race,” said Giovannoni, a professor in OSU’s College of Science. “Our analysis of the SAR11 genome indicates that they became the dominant life form in the oceans largely by being the simplest.”

“Their ability to cleave off methane is an interesting finding because it provides a partial explanation for why methane is so abundant in the high-oxygen waters of the mid-ocean regions,” Giovannoni added. “Just how much they contribute to the methane budget still needs to be determined.”

Since the discovery of SAR11, scientists have been interested in their role in the Earth’s carbon budget. Now their possible implication in methane creation gives the study of these bacteria new importance.

If our reporting has informed or inspired you, please consider making a donation. Every contribution, no matter the size, empowers us to continue delivering accurate, engaging, and trustworthy science and medical news. Independent journalism requires time, effort, and resources—your support ensures we can keep uncovering the stories that matter most to you.

Join us in making knowledge accessible and impactful. Thank you for standing with us!