New research findings point toward a class of compounds that could be effective in combating infections caused by enterovirus D68, which has stricken children with serious respiratory infections and might be associated with polio-like symptoms in the United States and elsewhere.

The researchers have used a technique called X-ray crystallography to learn the precise structure of the original strain of EV-D68 on its own and when bound to an anti-viral compound called “pleconaril.” The ongoing research could lead to the development of drugs that inhibit infections caused by the most recent strains of the virus, said Michael G. Rossmann, Hanley Distinguished Professor of Biological Sciences at Purdue University.

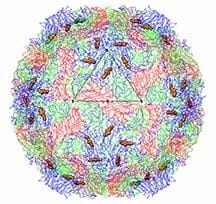

A molecule called a “pocket factor” is located within a pocket of the virus’s protective shell, called the capsid. When the virus binds to a human cell, the pocket factor is squeezed out of its pocket, resulting in the destabilization of the virus particle, which then disintegrates and releases its genetic material to infect the cell and to replicate itself.

The antiviral compound pleconaril also binds into the pocket, inhibiting infection.

“The compound and the normal pocket factor compete with each other for binding into the pocket,” Rossmann said. “They are both hydrophobic, and they both like to get away from water by going into the pocket. But which of these is going to win depends on the pocket itself, the pocket factor and properties of the antiviral compound.”

The findings are detailed in a paper appearing in the journal Science on Friday (Jan. 2). The paper was authored by Yue Liu, a graduate student; Ju Sheng, a technical assistant; Andrei Fokine, Geng Meng, Woong-Hee Shin, and Feng Long, post doctoral research associates; Richard Kuhn, professor and head of Purdue’s Department of Biological Sciences; Daisuke Kihara, a professor of biological sciences and computer science; and Rossmann.

A video interview with Rossmann and Liu is available at http://youtu.be/EXA01c0WL5o.

“In this work we only focused on the very original EV-D68 isolate, which was discovered in 1962,” Liu said. “Strains in the current outbreaks have minor differences.”

Although pleconaril is not active against current strains of EV-D68 tested thus far, it is active against the original isolate. Small changes in the structure of pleconaril are likely to lead to anti EV-D68 inhibitors against a broader spectrum of isolates.

An upsurge of EV-D68 cases in the past few years has been seen in clusters of infections worldwide. In August 2014 an outbreak of mild-to-severe respiratory illnesses occurred among thousands of children in the United States of which 1,149 cases have been confirmed to be caused by EV-D68. The virus also has been associated with occasional neurological infections and “acute flaccid myelitis,” characterized by symptoms including muscle weakness and paralysis. Although EV-D68 has emerged as a considerable global public health threat, there is no available vaccine or effective antiviral treatment.

Research led by Rossmann, working with pharmaceutical companies, has resulted in antiviral drugs for other enteroviruses such as rhinoviruses that cause common cold symptoms. These drugs include pleconaril, which was developed in the 1990s but not approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration primarily because of a side effect that puts women using birth control drugs at risk of conception.

Purdue researchers became interested in studying pleconaril’s potential effectiveness against EV-D68 after an outbreak of about 20 cases of acute flaccid paralysis was reported in California between 2012 and 2014. Out of those cases, two tested positive for EV-D68.

“This suggests the potential association of EV-D68 with polio-like illness,” Liu said.

The researchers are working with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and are studying the newer strains to determine their structures.

“The need for an effective antiviral agent for treatment of EV-D68 infections was made apparent by the widespread and large numbers of EV-D68 infections (in 2014), many of which were associated with significant morbidity,” said Mark A. McKinlay, director of the Center for Vaccine Equity at the Task Force for Global Health. “The determination of the structure of the EV-D68 reported here by Michael Rossmann and his team represents an important step in this direction. The strain of EV-D68 used in the study is from 1962, and Michael’s team, along with Steve Oberste’s group at CDC have shown that this strain is inhibited by pleconaril at clinically achievable concentrations. Testing of pleconaril against the current circulating strains at CDC thus far showed these strains are not susceptible to the antiviral compound.”

McKinlay, who collaborates with the CDC on polio eradication efforts, has been a key figure in pharmaceutical-company collaborations with Rossmann’s group to discover and develop pleconaril.

Once the newer strains are better understood, the ongoing research could yield compounds that are effective against these strains.

“Designing the best possible compound for these newer strains will take more time, but I hope that in a year or so we might have something,” Rossmann said.

Rossmann and Kuhn as well as David Stuart’s team in Oxford, England, working with Zihe Rao’s group in Beijing were among the first scientists to reveal important details of the structure of enterovirus 71, or EV71, which causes hand, foot and mouth disease, and is common throughout the world. Although that disease usually is not fatal, the virus has been reported to cause fatal encephalitis in infants and young children, primarily in the Asia-Pacific region.

Rossmann’s and Kuhn’s collaborative research has looked at virus structures in complex with receptors that permit entry of the virus into cells, and inhibitors of virus replication for a variety of viruses.

Like EV-D68 and EV71, poliovirus is an enterovirus and is within the large family called picornaviruses. Non-polio enteroviruses are common viruses and cause about 10 to 15 million infections in the United States each year, but most infected individuals have only mild illness, similar to a common cold, according to the CDC.

The research was supported by the National Institutes of Health.

If our reporting has informed or inspired you, please consider making a donation. Every contribution, no matter the size, empowers us to continue delivering accurate, engaging, and trustworthy science and medical news. Independent journalism requires time, effort, and resources—your support ensures we can keep uncovering the stories that matter most to you.

Join us in making knowledge accessible and impactful. Thank you for standing with us!