Two drugs that treat macular degeneration are practically interchangeable — except for the price.

Ranibizumab costs up to $2,000 per dose, while bevacizumab is $50 per dose. Researchers at the Stanford University School of Medicine suspected that doctors treating Medicare patients would have a financial incentive to prescribe a more costly drug. So they would be more likely to prescribe ranibizumab than doctors in the Veterans Health Administration, who do not have that incentive — right?

As it turns out, the prescription practices for these two drugs aren’t that straightforward, the researchers write in a paper published Feb. 2 in Health Affairs.

“It’s complicated,” said senior author Kate Bundorf, MBA, MPH, PhD, associate professor of health research and policy. “The incentives facing physicians don’t seem to be the only story.”

Researchers examined data from both systems from 2005-11. In 2011, Medicare physicians prescribed the less costly bevacizumab (brand name Avastin) 63 percent of the time. Ranibizumab (Lucentis) was prescribed 37 percent of the time. If all of those injections had been reimbursed at the rate for bevacizumab, Medicare would have saved approximately $1.1 billion, according to a 2011 report by the Office of Inspector General in the Department of Health and Human Services.

In the VA system, ranibizumab was prescribed 52 percent of the time in 2011. Interestingly, however, prescription decisions at the VA varied regionally, with some centers prescribing primarily bevacizumab, others primarily ranibizumab, and others alternating between the two drugs.

Possible effect of patient costs

Bundorf said she suspects that patients’ financial incentives may also be influencing prescribing decisions — that is, they may be asking for the less expensive drug, particularly if they’re covered by Medicare, whose patient co-pays sometimes reflect the cost of the drugs. Some physicians may also be thinking of the systemwide effects when selecting the less expensive drug, she said.

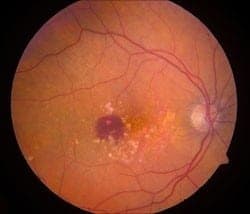

Both drugs are about equally effective at treating macular degeneration, the leading cause of visual impairment in older adults. Bevacizumab was originally developed to treat cancer, while ranibizumab was designed specifically for eye conditions.

Bundorf said the study illustrates the need for improvement in both health-care systems; for example, physicians could be offered incentives to select the best drug for the condition and save money.

Other Stanford co-authors are Suzann Pershing, MD, assistant professor of ophthalmology and chief of the ophthalmology section at the Veterans Affairs Palo Alto Health Care System; Christine Pal-Chee, PhD, associate at the Center for Health Policy and Center for Primary Care and Outcomes Research; Steven Asch, MD, MPH, professor of medicine at Stanford and chief of health services research at the VA-Palo Alto; Laurence Baker, PhD, professor of health research and policy; Derek Boothroyd, PhD, senior biostatistician; and Todd Wagner, PhD, consulting professor of health research and policy.

The study was supported by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality and the Department of Veterans Affairs. Information about Stanford’s Department of Health Research and Policy and Department of Ophthalmology, which also supported the work, is available at http://hrp.stanford.edu and http://ophthalmology.stanford.edu, respectively.

If our reporting has informed or inspired you, please consider making a donation. Every contribution, no matter the size, empowers us to continue delivering accurate, engaging, and trustworthy science and medical news. Independent journalism requires time, effort, and resources—your support ensures we can keep uncovering the stories that matter most to you.

Join us in making knowledge accessible and impactful. Thank you for standing with us!