For parents who send their kids to dance classes to get some exercise, a new study from researchers at University of California, San Diego School of Medicine suggests most youth dance classes provide only limited amounts of physical activity.

The study, published online May 18 in the journal Pediatrics, found that slightly more than one-third of class time, on average, was spent engaged in moderate-to-vigorous physical activity. The remainder of class time was spent doing light activities such as standing, listening or stretching, according to researchers, who analyzed activity levels of girls ages five to 18 participating in a variety of dance class types.

“This is a very commonly used opportunity for young people, especially girls, to be physically active and we find that they are inactive most of the time during dance classes,” said senior author James Sallis, PhD, professor in the Department of Family Medicine and Public Health. “We see this as a missed opportunity to get kids healthier.”

Approximately half of American youth do not meet U.S. Centers for Disease Control & Prevention (CDC) physical activity guidelines. The guidelines call for children and adolescents (6-17 years) to engage in at least 60 minutes of physical activity daily. Most of that time should be either moderate-or vigorous-intensity aerobic physical activity, say the guidelines. The CDC also recommends that schools provide 30 minutes of that time and after-school activites supply the remaining 30 minutes.

According to the Pediatrics study, participants recorded an average of 17 minutes of moderate-to-vigorous physical activity per class, but the figure varied by age and dance type. Class time averaged 49 minutes. “Overall, physical activity in youth dance classes was low,” said Sallis. “The study showed 8 percent of children and 6 percent of adolescents met the CDC’s 30-minute recommendation for after-school physical activity during dance.”

Two-hundred and sixty-four girls from 66 dance classes participated in the study, which collected data at 17 private studios and 4 community centers in San Diego County. Physical activity was measured with accelerometers, special devices worn around the waist which recorded intensity of movement every 15 seconds.

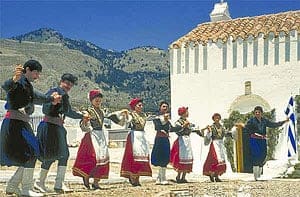

The researchers tracked their participants in two groups, children ages 5 – 10 and adolescents ages 11 to 18. They found that children were more active than adolescents in nearly all dance styles. They also saw activity variation based on type of dance. We found that not all dance types are created equal,” said Kelli Cain, the study’s first author. Seven dance types were included in the study: ballet; jazz; hip-hop; flamenco; salsa/ballet folklorico; tap; and partnered dance (which included ballroom, merengue, and swing).

“For example, hip-hop came out among the top in activity level for both children and adolescents while flamenco was the least active for both groups,” said Cain. In children, hip-hop averaged 57 percent of class time engaged in moderate-to-vigorous physical activity, while flamenco averaged about 14 percent of class time in such activity.

“Though there are important social, developmental, cultural and aesthetics benefits of dance that should be maintained and strengthened, it should be possible to increase physical activity,” said Sallis, noting there are an estimated 32,000 private dance studios in the U.S. as well as dance taught through school physical education classes and after-school programs.

Sallis said he hopes dance instructors will adopt the CDC’s 30-minute after school activity recommendation in their classes. The researchers suggested this could be accomplished through making warm-up periods more vigorous, having more frequent and longer practices of dance moves and including a segment of vigorous exercise in each class to improve fitness. Another strategy would be to emphasize greater participation in dance class types with higher levels of physical activity.

Making dance classes more active is critically important because of its popularity with girls, said Sallis. Past research suggests girls are less physically active than boys, beginning as early as preschool. “People are very concerned about the level of obesity in the U.S. among youth and how it has risen so dramatically. The more we study it, the more we find out how many ways young people are not very active. Boys don’t get enough exercise and girls get even less.”

The new findings build upon previous research by Sallis looking at other popular youth activities. In 2010, while a researcher at San Diego State University, Sallis examined physical activity in multiple popular youth sports. He found that only about one-fourth of children participating in organized sports — such as baseball, softball or soccer — received the government-recommended amount of physical activity during team practices.

“Nothing improves youth physical and mental health in as many ways as physical activity,” said Sallis. “That is why our research group is examining multiple strategies for creating more opportunities for young people to be physically active at home, at school, and throughout the community.”

Co-authors include Kavita Gavand, and Patricia Rincon, UCSD; Terry Conway, Edith Bonilla, and Nicole Bracy, UCSD and San Diego State University; Emma Peck, San Diego State University.

If our reporting has informed or inspired you, please consider making a donation. Every contribution, no matter the size, empowers us to continue delivering accurate, engaging, and trustworthy science and medical news. Independent journalism requires time, effort, and resources—your support ensures we can keep uncovering the stories that matter most to you.

Join us in making knowledge accessible and impactful. Thank you for standing with us!