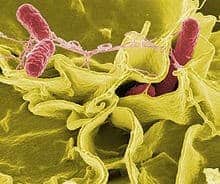

A new study from the Institute of Food Research has uncovered a mechanism by which Salmonella bacteria organise the expression of genes required for infection.

Salmonella bacteria are the leading cause of food borne illness in the EU. Part of what makes them so successful is their ability to invade our bodies, overcoming our natural defences. Understanding how they do this could lead to new ways of preventing their invasion.

Most Salmonella infections result in gastroenteritis, when the bacteria invade the epithelial cells lining our gut. However, under certain conditions, Salmonella can subsequently cause a potentially lethal systemic typhoidal infection when they invade the underlying immune cells. The invasion of epithelial cells and immune cells are controlled by two separate gene clusters called Salmonella Pathogenicity Islands 1 and 2 (SPI1, SPI2) respectively.

Now, in research published in the journal PLOS ONE, Dr Arthur Thompson and colleagues from the Institute of Food Research have shown how certain factors within Salmonella help to coordinate the deployment of SPI1 and SPI2.

The control system involves two proteins (RpoS and DksA) and ppGpp, an alarmone. Alarmones are molecules that bacteria produce in response to extreme environments, such as in the harsh environment of the gut. In conjunction with each other, these components help to coordinate when and where SPI1 and SPI1 genes are expressed, in phases that match the steps in Salmonella‘s infection strategy.

“We’ve shown how RpoS, DskA and ppGpp modulate the distribution and activity of RNA polymerase to allow the phased expression of SPI1 and SPI2” said Dr Thompson of the IFR, which is strategically funded by the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council. “This helps answer a longstanding and important question of how expression of SPI1 and SPI2 genes are synchronised which can result in a potentially fatal infection”.

If our reporting has informed or inspired you, please consider making a donation. Every contribution, no matter the size, empowers us to continue delivering accurate, engaging, and trustworthy science and medical news. Independent journalism requires time, effort, and resources—your support ensures we can keep uncovering the stories that matter most to you.

Join us in making knowledge accessible and impactful. Thank you for standing with us!