An important agricultural region in China is drying out, and increased farming may be more to blame than rising temperatures and less rain, according to a study spanning 30 years of data.

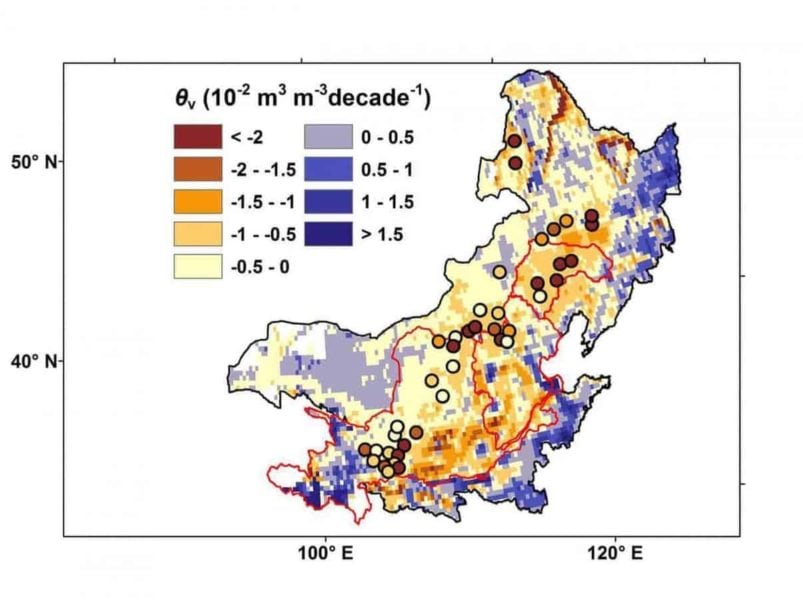

A research team led by Purdue University and China Agricultural University analyzed soil moisture during the growing season in Northern China and found that it has decreased by 6 percent since 1983.

The optimal soil-moisture level for farmland is typically 40 percent to 85 percent of the water holding capacity, and the region’s soil is now less than 40 percent and getting drier. If this trend continues, the soil may not be able to support crops by as early as 2090, said study leader Qianlai Zhuang, Purdue’s William F. and Patty J. Miller Professor of Earth, Atmospheric and Planetary Sciences and Agronomy.

“The soil moisture declined by 1.5 to 2.5 percent every decade of the study and, while climate change is still a factor, this water depletion appears to be largely driven by human activities,” Zhuang said. “A 10 percent decline in soil moisture over the course of a century would have major implications for agriculture and the fresh water supply in this heavily populated area.”

Forty percent of the nation’s population resides in Northern China, according to the country’s population census office. The region also accounts for 65 percent of the nation’s cropland, Zhuang said.

“The drying of soil in Northern China has been well documented, but its causes and the impacts of agricultural intensification in general have been understudied,” he said. “This information is critical to improvement of agricultural practices and water resource management. The demand for food and water is increasing, but current practices to meet this demand threaten the future security of water resources. Unfortunately, with the growing world population, more and more regions could face the same circumstances of agricultural intensification for food security.”

A paper detailing the results was published July 9 in Nature’s Scientific Reports journal and is currently available online.

In addition to Zhuang, co-authors from Purdue include Yaling Liu, a former graduate student in the Department of Earth, Atmospheric and Planetary Sciences who is now a postdoctoral researcher at the Pacific Northwest National Laboratory; Tonglin Zhang, an associate professor of statistics; and Dev Niyogi, a professor of Earth, Atmospheric and Planetary Sciences and Indiana State Climatologist. Additional co-authors include Zhihua Pan, Pingli An, Zhiqiang Dong, Jingtin Zhang, Di He, Liewei Wang and Xuebiao Pan of China Agricultural University in Beijing; Diego G. Miralles, of the University of Ghent in Belgium; and Adriaan J. Teuling, of the Hydrology and Quantitative Water Management Group of Wageningen University in The Netherlands.

The team obtained direct observations recorded at 40 monitoring stations set up by the Chinese government within agricultural plots, and used available data of fertilizer use and crop types since 1983. The team also used satellite remote sensing of water content on the soil’s surface and terrestrial water storage, meteorological observations and measurements of river discharge in their analysis.

The team also conducted a long-term study from 1983 to 2009 at two contiguous sites, one a pristine pasture and the other an agricultural site. The results showed a significant drying trend in the soil moisture in the cropland as opposed to a slight increase in the moisture of the pristine pasture soil.

The results showed a consistent trend in the reduction of soil moisture that correlated with increased fertilizer usage and the proliferation of crops with high water demands, like maize.

Fertilizer causes plants to grow larger and increases the number of leaves per plant. This leads to increased transpiration of water through pores on the leaves, called stomata. In addition, fertilizer use may aggravate soil compaction and soil salinity, which reduces the water holding capacity of soil and, consequently, reduces available soil water, Liu said.

“Fertilizer has been overused in China, which accounts for 31.4 percent of the total global consumption,” Liu said. “Although the negative effects of using fertilizer in excess of the needs of the crop is recognized in the scientific community, it is difficult to reverse the farming practices.”

While the increased use of fertilizer is not the only factor involved, the researchers found that it served as a broad diagnostic of the level of agricultural intensification. Other agricultural practices may also play a part in drying the land. For instance, newly developed crop varieties may demand more water and result in declining soil moisture, and increasing irrigation leads to rising withdrawals of surface freshwater and groundwater, she said.

“The results of this study underscore the importance of developing strategies for sustainable agriculture,” Liu said. “Perhaps crops that require less water could be substituted, water-saving technologies like mulching, reduced tillage, drip irrigation and improved soil-crop system management could be employed more broadly and advances in agricultural technology could improve the situation. The Chinese government is very interested in this issue, and this work was an important step in the road to sustainability.”

If our reporting has informed or inspired you, please consider making a donation. Every contribution, no matter the size, empowers us to continue delivering accurate, engaging, and trustworthy science and medical news. Independent journalism requires time, effort, and resources—your support ensures we can keep uncovering the stories that matter most to you.

Join us in making knowledge accessible and impactful. Thank you for standing with us!