Even before the onset of schizophrenia, irregularities in key brain areas are already present in individuals at higher risk of developing psychosis, a Yale-led study shows.

The findings identify a potential marker for the debilitating disease that afflicts 1% of the world’s population and suggest at least a partial explanation for why schizophrenia most typically manifests itself in young adulthood.

The new study, published online Aug. 12 in the journal JAMA Psychiatry, builds on work at Yale that shows schizophrenia is associated with marked alterations in connections between the thalamus, a major relay system in the brain, and the frontal cortex, which is involved in higher-level cognitive functions.

“Up until this study, we did not know whether this pattern was a result of the disease or a potential byproduct of medication or some other factor,” said Alan Anticevic, assistant professor of psychiatry and lead author of the paper. “We show these same abnormalities already exist in people who are at higher risk for developing psychosis.”

Schizophrenia usually develops late in adolescence or early adulthood but is often proceeded by some early warning signs such as mild suspicion, a perception that outside stimuli carry a special personal significance, or hearing a voice calling the individual’s name, said Tyrone Cannon, professor of psychology and senior author of the study.

In chronic schizophrenia, especially if untreated, these symptoms worsen and can become debilitating. It has been unclear exactly what brain mechanisms are responsible for its onset.

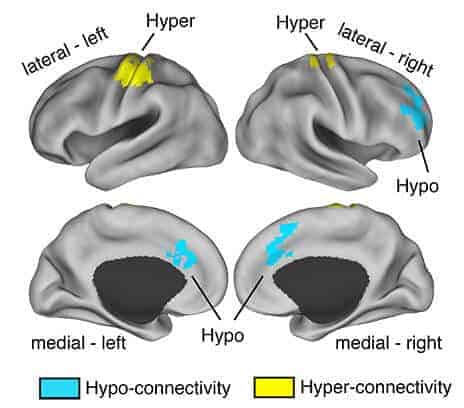

In an international multi-site study, researchers developed whole-brain functional connectivity maps of 243 people who experienced early warning symptoms and 154 healthy subjects, and then followed them for two years. They found a decrease in functional connectivity between the thalamus and prefrontal cortex regions in the at-risk group that was particularly pronounced in those who went on to develop full psychosis. However, the at-risk group also had excess connectivity between thalamus and sensory areas of the brain. This general pattern seen during these early stages of heightened risk resembled the changes seen in more chronic patients.

Cannon said more research needs to be done to definitively link disrupted functional connectivity between the thalamus and frontal cortex as a cause of schizophrenia. However, he noted that the study findings are consistent with the theory that those who develop schizophrenia experience an excessive reduction in synaptic connections between brain cells that normally occur during adolescence.

If our reporting has informed or inspired you, please consider making a donation. Every contribution, no matter the size, empowers us to continue delivering accurate, engaging, and trustworthy science and medical news. Independent journalism requires time, effort, and resources—your support ensures we can keep uncovering the stories that matter most to you.

Join us in making knowledge accessible and impactful. Thank you for standing with us!