Buried beneath the snow line,

these smouldering corpses

begin to glow.

Forgotten fires,

whose reanimated embers

burn brightly

across the tundra;

frozen bodies recoiling

at the heat

of their undying embrace.

Thawed to life by

distant warming

these undead hordes now

straddle horizons;

crimson fingers

flickering over

blue-veined memories,

as they dance

impossibly beyond

the water’s edge.

Nervously

we shift our gaze

towards a restless earth,

as unwanted resurrections

blaze across the landscape.

This poem is inspired by new research, which has found that the ways in which Arctic wildfires burn are potentially changing, with strong consequences for the global climate.

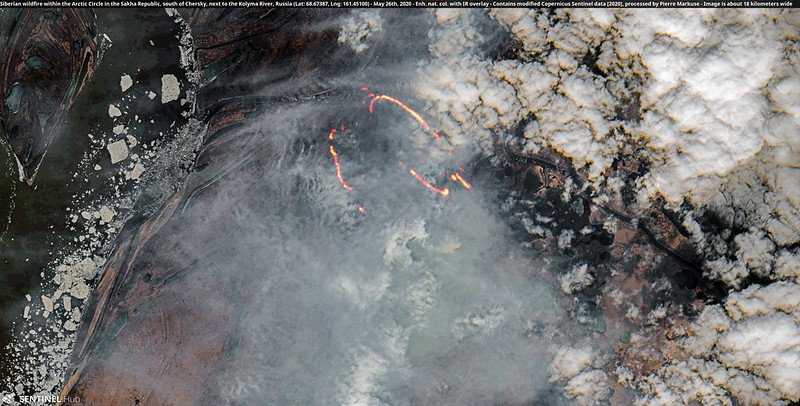

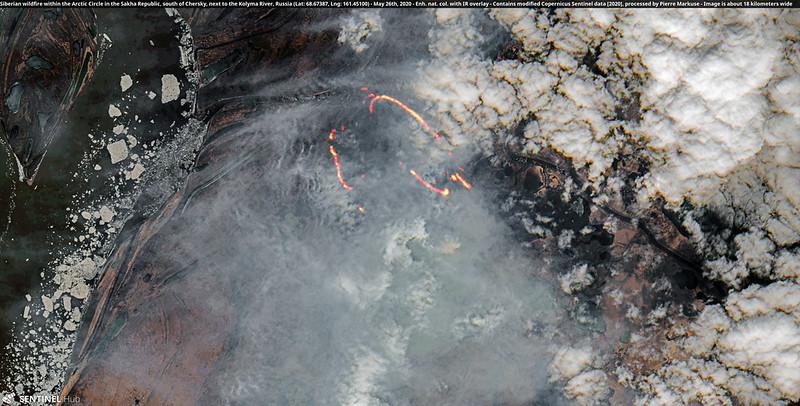

The 2020 Arctic wildfire season began two months early and was unprecedented in scope; in addition to the increase in severity and occurrence, two new features for the way in which these fires burn have also being identified. The first is what is known as holdover, or zombie, fires. These fires occur when fire from a previous growing season smoulders in carbon-rich peat underground over the winter, re-igniting on the surface several months (or even years) later, when the weather begins to warm. The second feature that has been observed is the occurrence of fire in what were previously thought to be fire-resistant landscapes. As the Arctic tundra becomes hotter and drier due to global warming, vegetation types such as sedges, grass, and moss, that are not typically thought of as fuels, start to catch fire. Even wet landscapes like bogs, fens, and marshes are also becoming vulnerable to burning in the changing climate.

More than half of the fires detected in Siberia this year were north of the Arctic Circle, occurring on permafrost that has a high percentage of ground ice. This type of permafrost contains enormous amounts of carbon, and global climate models currently do not account for their rapid thawing and subsequent release of greenhouse gases. At the local level, the rapid thawing of this permafrost would result in subsidence, floods, and landslides. Understanding these new fire regimes is therefore essential in order to better understand the impact that they will have on both the local and global level. However, while satellite imagery could potentially help to map the extent and timing of these new surface fires, measurements made on the ground are still needed to help calibrate any observations that are made by satellites. As such, addressing the gaps in our current understanding will require critical input from Indigenous and local communities, as well as collaboration across many different scientific disciplines.

If our reporting has informed or inspired you, please consider making a donation. Every contribution, no matter the size, empowers us to continue delivering accurate, engaging, and trustworthy science and medical news. Independent journalism requires time, effort, and resources—your support ensures we can keep uncovering the stories that matter most to you.

Join us in making knowledge accessible and impactful. Thank you for standing with us!