One of North America’s most famous fossil discoveries has finally been properly identified as a new species of giant marine reptile that hunted the prehistoric seas 85 million years ago.

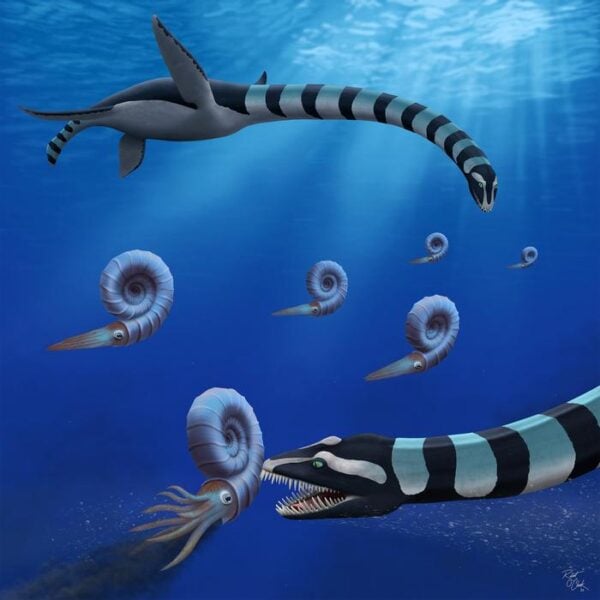

Traskasaura sandrae, a 12-meter-long elasmosaur with crushing teeth and a distinctive hunting style, represents a crucial piece in understanding how these ancient sea monsters evolved and spread across the world’s oceans. The fossils, first discovered in 1988 along Vancouver Island’s Puntledge River, became British Columbia’s official provincial fossil in 2023 before scientists could even determine what species they belonged to—a testament to both their fame and their puzzling nature.

The Fossil That Defied Classification

The story began when Michael and Heather Trask discovered the first specimen along the Puntledge River banks. Since then, two additional fossils have emerged: a well-preserved juvenile skeleton and an isolated arm bone, providing scientists with a complete picture of this marine predator.

What made classification so difficult was Traskasaura’s unusual combination of features. “The scientific confusion concerning this taxon is understandable. It has a very odd mix of primitive and derived traits,” explained lead author Professor F. Robin O’Keefe from Marshall University. “The shoulder, in particular, is unlike any other plesiosaur I have ever seen, and I have seen a few.”

The creature possessed heavy, robust teeth ideal for crushing—likely targeting the abundant ammonites (spiral-shelled marine animals) that shared its ancient Pacific habitat. These teeth were “round with prominent longitudinal striations around entire circumference,” a unique feature that helped distinguish it from other elasmosaurs.

A Predator From Above

What emerges from the detailed analysis is a picture of an innovative hunter. Traskasaura’s unique skeletal adaptations suggest it was among the first plesiosaurs to hunt prey from above, diving down on unsuspecting victims in the ancient seas.

The creature’s shoulder joint faced downward and outward rather than straight to the side, enabling specialized swimming motions. Its limb bones showed pronounced “ventral camber”—more curved on the bottom than the top—suggesting an emphasis on powerful downward swimming strokes.

The research reveals that Traskasaura had an unusually straight arm bone shaft, unlike the angled shafts typical of other marine reptiles of its era. This seemingly minor anatomical detail actually represents a fundamentally different approach to underwater locomotion.

Key Distinguishing Features:

- 12-meter body length with at least 50 neck vertebrae

- Specialized shoulder joint angled for downward swimming

- Robust, striated teeth designed for crushing shells

- Straight limb bone shafts unlike other contemporary species

- Four bone elements in the flipper structure instead of the typical three

Evolutionary Puzzle Pieces

The detailed study reveals something particularly intriguing about marine reptile evolution. Traskasaura shared several features with a group called aristonectines—specialized filter-feeding elasmosaurs from the southern Pacific. However, the phylogenetic analysis showed these similarities evolved independently, representing convergent evolution rather than close relationship.

This finding reshapes understanding of how marine reptiles adapted to different ecological niches. The research demonstrates that similar environmental pressures can produce similar anatomical solutions in completely unrelated lineages, even across vast ocean basins.

The study also provides crucial insight into the biogeography of ancient marine ecosystems. While true aristonectines were restricted to the southern Pacific, northern hemisphere animals like Traskasaura developed similar adaptations independently, suggesting that certain ecological niches drove predictable evolutionary responses.

Ancient Pacific Geography

The fossils come from the Haslam Formation, deposited in a narrow ocean basin between 86.3 and 83.6 million years ago. At the time, Vancouver Island was much farther south—possibly near the latitude of modern-day Oregon or southern Japan.

This ancient marine environment was rich with life. The rock layers contain “abundant trace fossils, foraminifera, diverse ammonoids, gastropods, decapod crustaceans and crinoids,” painting a picture of a thriving ecosystem that supported large marine predators like Traskasaura.

The presence of abundant ammonoids in the same rock layers supports the hypothesis that these spiral-shelled creatures were Traskasaura’s preferred prey. The elasmosaur’s robust teeth would have been “ideal, possibly, for crushing ammonite shells,” according to Professor O’Keefe.

The Naming Story

The genus name honors Michael and Heather Trask, the discoverers of the original specimen. The species name “sandrae honours Sandra Lee O’Keefe (née Markey),” who was described as “a valiant warrior in the fight against breast cancer. In loving memory.”

This personal touch reflects the human stories behind scientific discovery—both the amateur fossil hunters who make crucial finds and the researchers who dedicate their careers to understanding ancient life.

The path from discovery to description took 37 years, highlighting the careful, methodical nature of paleontological research. As O’Keefe noted, “The fossil record is full of surprises. It is always gratifying to discover something unexpected.”

Implications for Understanding Ancient Seas

Traskasaura’s discovery adds another piece to the complex puzzle of Cretaceous marine ecosystems. The creature lived during a time of significant environmental change, when sea levels were high and marine reptiles had diversified into numerous specialized niches.

The research suggests that early elasmosaurs were more diverse in their hunting strategies than previously recognized. While some evolved into filter-feeders with hundreds of tiny teeth, others like Traskasaura became precision predators with powerful crushing jaws.

Understanding these ancient marine ecosystems becomes increasingly important as modern oceans face unprecedented changes. The fossil record provides crucial baselines for understanding how marine life responds to environmental pressures—lessons that may prove vital for conservation efforts today.

As Professor O’Keefe concluded, “With the naming of Traskasaura sandrae, the Pacific Northwest finally has Mesozoic reptile to call its own. Fittingly, a region known for its rich marine life today was host to strange and wonderful marine reptiles in the Age of Dinosaurs.”

If our reporting has informed or inspired you, please consider making a donation. Every contribution, no matter the size, empowers us to continue delivering accurate, engaging, and trustworthy science and medical news. Independent journalism requires time, effort, and resources—your support ensures we can keep uncovering the stories that matter most to you.

Join us in making knowledge accessible and impactful. Thank you for standing with us!