Ancient fossilized footprints have provided scientists with unprecedented insight into when and how pterosaurs – the magnificent flying reptiles that soared above dinosaurs – developed the ability to walk efficiently on land, according to groundbreaking research published in Current Biology on May 1.

A team of paleontologists from the University of Leicester successfully matched three distinct pterosaur track types to specific pterosaur groups, effectively solving an 88-year-old mystery about which flying reptiles created these prehistoric footprints and what they reveal about pterosaur evolution.

Mid-Mesozoic Ecological Shift Confirmed

The study provides compelling evidence for a major ecological transition approximately 160 million years ago, when several pterosaur groups evolved to become more terrestrially adapted. This contradicts earlier perceptions of pterosaurs as primarily aerial specialists with limited ground mobility.

“Footprints offer a unique opportunity to study pterosaurs in their natural environment,” explained lead author Robert Smyth, a doctoral researcher at the University of Leicester. “They reveal not only where these creatures lived and how they moved, but also offer clues about their behaviour and daily activities in ecosystems that have long since vanished.”

Co-author Dr. David Unwin added, “Finally, 88 years after first discovering pterosaur tracks, we now know exactly who made them and how.”

Three Distinct Walking Styles Identified

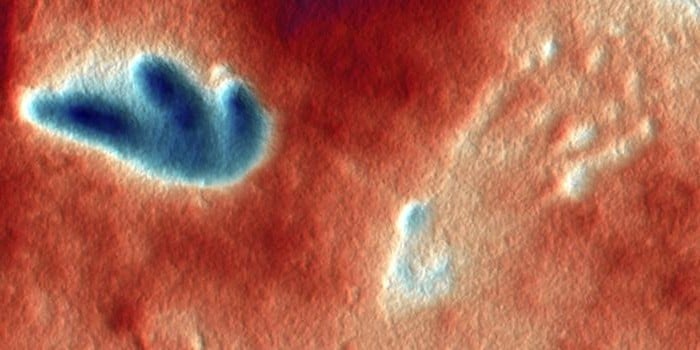

Using 3D modeling, detailed anatomical analysis, and comparisons with pterosaur skeletons, researchers identified specific features in the footprints that matched perfectly with the foot anatomy of three pterosaur groups:

- Ctenochasmatoids – filter-feeding waders with elongated jaws and needle-like teeth that left footprints primarily in coastal environments

- Dsungaripterids – specialized shellfish-eaters whose tracks appear alongside their skeletal remains in the same rock layers

- Neoazhdarchians – including the largest flying animals ever, which left footprints in diverse environments right up until the extinction event 66 million years ago

Expanding Our Understanding of Prehistoric Ecosystems

What makes these findings particularly valuable is how they complement and extend what we know from body fossils alone. The footprint record shows that neoazhdarchians frequently inhabited the same environments as many dinosaur species, supporting theories that these long-legged pterosaurs spent considerable time walking on the ground.

Perhaps most surprisingly, the absence of any footprints from non-pterodactyloid pterosaurs (an earlier evolutionary group) supports the hypothesis that these primitive pterosaurs were primarily adapted for climbing trees or rocky surfaces rather than walking on flat ground.

Filling Critical Gaps in the Fossil Record

Can footprints tell us more about pterosaur populations than their skeletal remains? In many cases, the answer appears to be yes. The abundance of coastal ctenochasmatoid tracks suggests these pterosaurs were far more common in these environments than their relatively rare skeletal fossils would indicate.

“Tracks are often overlooked when studying pterosaurs, but they provide a wealth of information about how these creatures moved, behaved, and interacted with their environments,” Smyth explained. “By closely examining footprints, we can now discover things about their biology and ecology that we can’t learn anywhere else.”

The research transforms our understanding of pterosaur evolution and ecological significance. Rather than being confined to aerial niches, successive groups of pterosaurs maintained a strong presence across diverse terrestrial environments throughout the latter half of the Mesozoic era, highlighting their remarkable adaptability and evolutionary success.

This integration of body fossils and trace fossils demonstrates that pterosaurs underwent a major radiation into terrestrial niches beginning in the Middle Jurassic, fundamentally changing our perception of these iconic prehistoric creatures and their role in ancient ecosystems.

If our reporting has informed or inspired you, please consider making a donation. Every contribution, no matter the size, empowers us to continue delivering accurate, engaging, and trustworthy science and medical news. Independent journalism requires time, effort, and resources—your support ensures we can keep uncovering the stories that matter most to you.

Join us in making knowledge accessible and impactful. Thank you for standing with us!