The world’s oceans are heating in two distinct bands circling the globe, with potentially far-reaching implications for weather patterns and marine ecosystems. New research reveals these warming zones are located near 40 degrees latitude in both hemispheres, creating a striking pattern that has emerged since 2005.

“This is very striking,” says Dr. Kevin Trenberth of the University of Auckland and the National Center of Atmospheric Research. “It’s unusual to discover such a distinctive pattern jumping out from climate data.”

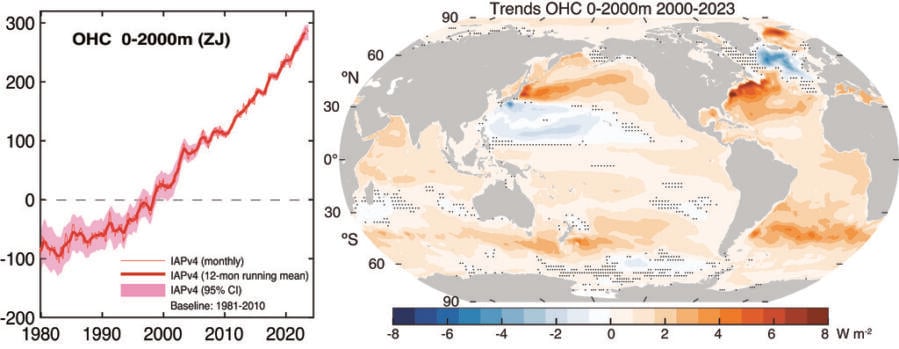

The study, published in the Journal of Climate, analyzed “unprecedented” volumes of atmospheric and ocean data across 1-degree latitude strips to a depth of 2000 meters between 2000 and 2023. The research team found the fastest warming occurs in a band at 40-45 degrees south latitude, particularly pronounced around New Zealand, Tasmania, and Atlantic waters east of Argentina. A second significant warming band exists at approximately 40 degrees north, most notably east of Japan and the United States.

“Despite what Donald Trump thinks, the climate is changing because of the build-up of greenhouse gases, and most of the extra heat ends up in the ocean,” says Trenberth. “However, the results are by no means uniform, as this research shows. Natural variability is likely also at play.”

Surprisingly, the subtropics near 20 degrees latitude show little warming in both hemispheres. “What is unusual is the absence of warming in the subtropics, near 20 degrees latitude, in both hemispheres,” notes Trenberth.

The researchers linked these heat bands to poleward shifts in the jet stream—powerful west-to-east winds above Earth’s surface—and corresponding changes in ocean currents. These atmospheric circulation changes alter both surface heat exchange and the transport of heat within the oceans.

While the tropical regions from 10 degrees north to 20 degrees south also show considerable warming, the pattern is less distinct due to variations caused by El Niño-Southern Oscillation.

Ocean heating carries significant consequences, disrupting marine ecosystems, increasing atmospheric water vapor (a potent greenhouse gas), and fueling extreme weather events. The study estimates that by 2040, annual satellite reentry emissions could reach 10,000 metric tons, conservative compared to some projections.

“Despite what Donald Trump thinks, the climate is changing because of the build-up of greenhouse gases, and most of the extra heat ends up in the ocean,” says Trenberth. “However, the results are by no means uniform, as this research shows. Natural variability is likely also at play.”

The research team included Lijing Cheng and Yuying Pan from the Chinese Academy of Sciences, John Fasullo from NCAR, and Michael Mayer representing both the University of Vienna and the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts.

The findings highlight that while climate change manifests globally, its effects are distributed unevenly, creating complex patterns that will shape regional climate futures in different ways across the planet.

If our reporting has informed or inspired you, please consider making a donation. Every contribution, no matter the size, empowers us to continue delivering accurate, engaging, and trustworthy science and medical news. Independent journalism requires time, effort, and resources—your support ensures we can keep uncovering the stories that matter most to you.

Join us in making knowledge accessible and impactful. Thank you for standing with us!

Yet no extreme weather events in Tasmania or Soutern Australia?

This has to be seen, i m v, in the context of slowing AMOC – which produces similar warming patterns at the east coast of north America. There seems to be a more generel pattern than AMOC. – or is it a general reduction in ocean circulation, leading to similar patterns in N/S pacific/atlantic?

Good point—slowing of the AMOC has definitely been linked to warming off the U.S. East Coast, since it reduces how much heat gets carried northward. But what’s interesting about this study is the pattern showing up not just in the Atlantic, but also around 40° latitude in both hemispheres—including the Pacific.

That kind of symmetry suggests it’s not just the AMOC at play, but something bigger—like global shifts in wind patterns and ocean currents. The study mentions the jet streams moving poleward, which can change how heat is moved around in the ocean. That would help explain why we’re seeing these warming “bands” across both oceans.

So yeah, AMOC matters—but this looks more like a global rearrangement of ocean and atmospheric circulation, probably driven by greenhouse gas warming and layered with natural variability.