The history of the peopling of the Americas has just been interpreted afresh. The largest and most comprehensive study ever conducted on the basis of fossil DNA extracted from ancient human remains found on the continent has confirmed the existence of a single ancestral population for all Amerindian ethnic groups, past and present.

Over 17,000 years ago this original contingent crossed the Bering Strait from Siberia to Alaska and began peopling the New World. Fossil DNA shows an affinity between this migratory current and the populations of Siberia and northern China. Contrary to the traditional theory it had no link to Africa or Australasia.

The new study also reveals that once they had settled in North America the descendants of this ancestral migratory flow diversified into two lineages some 16,000 years ago.

The members of one lineage crossed the Isthmus of Panama and peopled South America in three distinct consecutive waves.

The first wave occurred between 15,000 and 11,000 years ago. The second took place at most 9,000 years ago. There are fossil DNA records from both migrations throughout South America. The third wave is much more recent but its influence is limited as it occurred 4,200 years ago. Its members settled in the Central Andes.

An article on the study has just been published in the journal Cell a group of 72 researchers from eight countries, affiliated with the University of São Paulo (USP) in Brazil, Harvard University in the United States, and Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History in Germany, among others.

According to the researchers’ findings, the lineage that made the north-south journey between 16,000 and 15,000 years ago belonged to the Clovis culture, named for a group of archeological sites excavated in the western US and dating from 13,500-11,000 years ago.

The Clovis culture was so named when flint spearheads were found in the 1930s at a dig in Clovis, New Mexico. Clovis sites have been identified throughout the US and in Mexico and Central America. In North America, the Clovis people hunted Pleistocene megafaunas such as giant sloth and mammoth. With the decline of the megafauna and its extinction 11,000 years ago, the Clovis culture eventually disappeared. Long before that, however, bands of hunter-gatherers had traveled south to explore new hunting grounds. They ended up settling in Central America, as evidenced by 9,400-year-old human fossil DNA found in Belize and analyzed in the new study.

At a later date, perhaps while pursuing herds of mastodons, Clovis hunter-gatherers crossed the Isthmus of Panama and spread into South America, as evidenced by genetic records from burial sites in Brazil and Chile revealed now. This genetic evidence corroborates well-known archeological finds such as the Monte Verde site in southern Chile, where humans butchered mastodons 14,800 years ago.

Among the many known Clovis sites, the only burial site associated with Clovis tools is in Montana, where the remains of a baby boy (Anzick-1) were found and dated to 12,600 years ago. DNA extracted from these bones has links to DNA from skeletons of people who lived between 10,000 and 9,000 years ago in caves near Lagoa Santa, Minas Gerais State, Brazil. In other words, the Lagoa Santa people were partial descendants of Clovis migrants from North America.

“From the genetic standpoint, the Lagoa Santa people are descendants of the first Amerindians,” said archeologist André Menezes Strauss, who coordinated the Brazilian part of the study. Strauss is affiliated with the University of São Paulo’s Museum of Archeology and Ethnology (MAE-USP).

“Surprisingly, the members of this first lineage of South Americans left no identifiable descendants among today’s Amerindians,” he said. “Some 9,000 years ago their DNA disappears completely from the fossil samples and is replaced by DNA from the first migratory wave, prior to the Clovis culture. All living Amerindians are descendants of this first wave. We don’t yet know why the genetic stock of the Lagoa Santa people disappeared.”

One possible reason for the disappearance of DNA from the second migration is that it was diluted in the DNA of the Amerindians who are descendants of the first wave and cannot be identified by existing methods of genetic analysis.

According to Tábita Hünemeier, a geneticist at the University of São Paulo’s Bioscience Institute (IB-USP) who took part in the research, “one of the main results of the study was the identification of Luzia’s people as genetically related to the Clovis culture, which dismantles the idea of two biological components and the possibility that there were two migrations to the Americas, one with African traits and the other with Asian traits”.

“Luzia’s people must have resulted from a migratory wave originating in Beringia,” she said, referring to the now-submerged Bering land bridge that joined Siberia to Alaska during the glaciations, when sea levels were lower.

“The molecular data suggests population substitution in South America since 9,000 years ago. Luzia’s people disappeared and were replaced by the Amerindians alive today, although both had a common origin in Beringia,” Hünemeier said.

Brazilian contribution

The Brazilian researchers’ contribution to the study was fundamental. Among the 49 individuals from which fossil DNA was taken, seven skeletons dated to between 10,100 and 9,100 years ago came from Lapa do Santo, a rock shelter in Lagoa Santa.

The seven skeletons, alongside dozens of others, were found and exhumed in successive archeological campaigns at the site, led initially by Walter Alves Neves, a physical anthropologist at IB-USP, and since 2011 by Strauss. The archeological campaigns led by Neves between 2002 and 2008 were funded by São Paulo Research Foundation – FAPESP.

Altogether the new study investigated fossil DNA from 49 individuals found at 15 archeological sites in Argentina (two sites, 11 individuals dated to between 8,900 and 6,600 years ago), Belize (one site, three individuals dated to between 9,400 and 7,300 years ago), Brazil (four sites, 15 individuals dated to between 10,100 and 1,000 years ago), Chile (three sites, five individuals dated to between 11,100 and 540 years ago) and Peru (seven sites, 15 individuals dated to between 10,100 and 730 years ago).

The Brazilian skeletons come from the archeological sites Lapa do Santo (seven individuals dated to about 9,600 years ago), Jabuticabeira II in Santa Catarina State (a sambaqui or shell midden with five individuals dated to about 2,000 years ago), as well as from two river middens in the Ribeira Valley, São Paulo State: Laranjal (two individuals dated to about 6,700 years ago), and Moraes (one individual dated to about 5,800 years ago).

Paulo Antônio Dantas de Blasis, an archeologist affiliated with MAE-USP, led the dig at Jabuticabeira II, which was also supported by FAPESP through a Thematic Project.

The digs at the river midden sites in São Paulo State were led by Levy Figuti, also an archeologist at MAE-USP, and were also supported by FAPESP.

“The Moraes skeleton (5,800 years old) and the Laranjal skeleton (6,700 years old) are among the most ancient from the South and Southeast of Brazil,” Figuti said. “These locations are strategically unique because they’re between the highlands of the Atlantic plateau and the coastal plain, contributing significantly to our understanding of how the Southeast of Brazil was peopled.”

These skeletons were found between 2000 and 2005. From the start, they presented a complex mixture of coastal and inland cultural traits, and the results of their analysis generally varied except in the case of one skeleton diagnosed as Paleoindian (analysis of its DNA is not yet complete).

“The study that’s just been published represents a major step forward in archeological research, exponentially increasing what we knew until only a few years ago about the archaeogenetics of the peopling of the Americas,” Figuti said.

Hünemeier has also recently made a significant contribution to the reconstruction of human history in South America using paleogenomics.

Amerindian genetics

Not all the human remains found at some of the most ancient archeological sites in Central and South America belonged to genetic descendants of the Clovis culture. The inhabitants of several sites did not have Clovis-associated DNA.

“This shows that besides its genetic contribution the second migration wave to South America, which was Clovis-associated, may also have brought with it technological principles that would be expressed in the famous fishtail points that are found in many parts of South America,” Strauss said.

How many human migrations from Asia came to the Americas at the end of the Ice Age more than 16,000 years ago was hitherto unknown. The traditional theory, formulated in the 1980s by Neves and other researchers, was that the first wave had African traits or traits similar to those of the Australian Aboriginals.

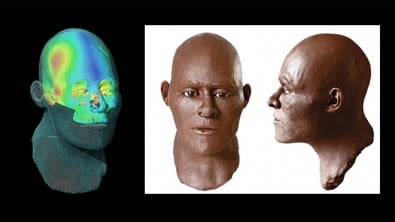

The well-known forensic facial reconstruction of Luzia was performed in accordance with this theory. Luzia is the name given to the fossil skull of a woman who lived in the Lagoa Santa region 12,500 years ago and is sometimes referred to as the “first Brazilian”.

The bust of Luzia with African features was built on the basis of the skull’s morphology by British anatomical artist Richard Neave in the 1990s.

“However, skull shape isn’t a reliable marker of ancestrality or geographic origin. Genetics is the best basis for this type of inference,” Strauss explained.

“The genetic results of the new study show categorically that there was no significant connection between the Lagoa Santa people and groups from Africa or Australia. So the hypothesis that Luzia’s people derived from a migratory wave prior to the ancestors of today’s Amerindians has been disproved. On the contrary, the DNA shows that Luzia’s people were entirely Amerindian.”

A new bust has replaced Luzia in the Brazilian scientific pantheon. Caroline Wilkinson, a forensic anthropologist at Liverpool John Moores University in the UK and a disciple of Neave, has produced a facial reconstruction of one of the individuals exhumed at Lapa do Santo. The reconstruction was based on a retrodeformed digital model of the skull.

“Accustomed as we are to the traditional facial reconstruction of Luzia with strongly African features, this new facial reconstruction reflects the physiognomy of the first inhabitants of Brazil far more accurately, displaying the generalized and indistinct features from which the great Amerindian diversity was established over thousands of years,” Strauss said.

The study published in Cell, he added, also presents the first genetic data on Brazilian coastal sambaquis.

“These monumental shell mounds were built some 2,000 years ago by populous societies that lived on the coast of Brazil. Analysis of fossil DNA from shell mound burials in Santa Catarina and São Paulo shows these groups were genetically akin to the Amerindians alive today in the South of Brazil, especially the Kaingang groups,” he said.

According to Strauss, DNA extraction from fossils is technically very challenging, especially if the material was found at a site with a tropical climate. For almost two decades extreme fragmentation and significant contamination prevented different research groups from successfully extracting genetic material from the bones found at Lagoa Santa.

This has now been done thanks to methodological advances developed by the Max Planck Institute. As Strauss enthusiastically explained, much more remains to be discovered.

“Construction of Brazil’s first archaeogenetic laboratory is scheduled to begin in 2019, thanks to a partnership between the University of São Paulo’s Museum of Archeology and Ethnology (MAE) and its Bioscience Institute (IB) with funding from FAPESP. When it’s ready, it will give a new thrust to research on the peopling of South America and Brazil,” Strauss said.

“To some extent, this study not only changes what we know about how the region was peopled but also changes considerably how we study human skeletal remains,” Figuti said.

Human remains were first found in Lagoa Santa in 1844, when Danish naturalist Peter Wilhelm Lund (1801-1880) discovered some 30 skeletons deep in a flooded cave. Almost all these fossils are now at the Natural History Museum of Denmark in Copenhagen. A single skull has stayed in Brazil. It was donated by Lund to the Brazilian History and Geography Institute in Rio de Janeiro.

Colonization by leaps and bounds

On the same day as the Cell article was published (November 8, 2018), a paper in the journal Science also reported new findings on fossil DNA from the first migrants to the Americas. André Strauss is one of the authors.

Among the 15 ancient skeletons from which genetic material was taken, five belong to the Lund Collection in Copenhagen. They date from between 10,400 and 9,800 years ago. They are the oldest in the sample, alongside an individual from Nevada estimated to be 10,700 years old.

The sample comprised fossilized human remains from Alaska, Canada, Brazil, Chile, and Argentina. The results of its molecular analysis suggested the peopling of the Americas by the first human groups out of Alaska did not come about merely through gradual occupation of territory concomitantly with population growth.

According to the researchers responsible for the study, the molecular data suggests that the first humans to invade Alaska or neighboring Yukon, split into two groups. This happened between 17,500 and 14,600 years ago. One group colonized North and Central America, the other South America.

The peopling of the Americas ensued by leaps and bounds, as small bands of hunter-gatherers traveled far and wide to settle in new areas until they reached Tierra del Fuego in a movement lasting one or at most two millennia.

Among the 15 individuals whose DNA was analyzed, three of the Lagoa Santa five were found to have some genetic material from Australasia, as suggested by the theory proposed by Neves for the occupation of South America. The researchers are unable to explain the origin of this Australasian DNA or how it ended up in only a few of the Lagoa Santa people.

“The fact that the genomic signature of Australasia has been present for 10,400 years in Brazil but is absent in all the genomes tested to date, which are as old or older, and found farther north, is a challenge considering its presence in Lagoa Santa,” they said.

Other fossils collected during the twentieth century include the Luzia skull, found in the 1970s. Almost 100 skulls excavated by Neves and Strauss in the past 15 years are now held at USP. A similar number of fossils are held at the Pontifical Catholic University of Minas Gerais (PUC-MG).

But the vast majority of these osteological and archeological treasures, belonging to perhaps more than 100 individuals, were deposited at the National Museum in Rio de Janeiro and were presumably destroyed in the fire that raged through this historic building on September 2, 2018.

The Luzia skull was on display at the National Museum alongside Neave’s facial reconstruction. Scientists feared it had been lost to the fire but fortunately it was one of the first objects to be recovered from the ruins. It had broken up but survived. The fire destroyed the original facial reconstruction (of which there are several copies).

If our reporting has informed or inspired you, please consider making a donation. Every contribution, no matter the size, empowers us to continue delivering accurate, engaging, and trustworthy science and medical news. Independent journalism requires time, effort, and resources—your support ensures we can keep uncovering the stories that matter most to you.

Join us in making knowledge accessible and impactful. Thank you for standing with us!