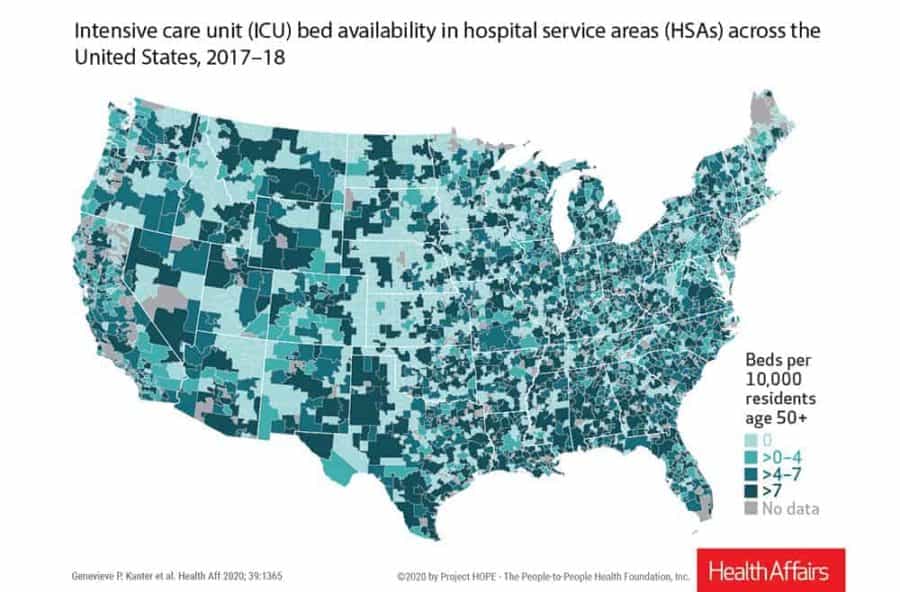

While the shortage of ICU beds in the United States has been documented since the pandemic began, the new report, published Monday in the August issue of Health Affairs, is the first to show how starkly a person’s ZIP code affects access to COVID-19 care. Most dramatically, approximately half of communities with the lowest median household incomes (less than $35,000) have zero ICU beds per ten thousand residents age fifty or older, compared with just 3 percent of communities with household incomes of at least $90,000.

ICU, or critical care units, provide life support and high-tech equipment for patients with serious, life-threatening illnesses who require continuous care and monitoring. In the case of COVID-19, patients who are unable to breathe on their own require the ventilator support offered by an ICU to survive. For seriously ill patients, having access to an ICU is the difference between life and death.

The findings suggest that policymakers must take action, such as facilitating hospital sharing and publicly financing specialized resources, said study principal investigator Genevieve P. Kanter, PhD, an assistant professor of Medicine, Medical Ethics, and Health Policy in the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania.

“Because low-income communities face higher infection rates of the virus, as well as a higher prevalence of comorbidities — which increases the risk of death from the disease — the low supply of ICU beds compounds the impact COVID-19 will have on these communities,” Kanter said. “Plans should be made for coordinating how hospitals can share these burdens.”

The study sample consisted of the ICU bed capacity of 4,518 short-term and critical access hospitals in the 50 states and Washington, D.C., obtained from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services’ Healthcare Provider Cost Reporting Information System. The researchers used 2018 five-year American Community Survey estimates to gather information about population, age distribution, racial distribution, and median household income. Rather than comparing ICU bed capacity by county or ZIP code, the researchers instead aggregated their data by hospital service area (HSA), which is defined as a set of ZIP codes corresponding to the area in which residents receive most of their hospital care.

The study found that ICU availability varied considerably across the country. More than one third of American communities had zero ICU beds. Geographically, half of hospital service areas in the Midwest census region and 34 percent in the West had zero ICU beds per then thousand residents age fifty or older. By contrast, 52 percent of hospital service areas in the Northeast and 54 percent in the South had more than four ICU beds per ten thousand residents age fifty or older

The researchers also found a large gap in access by income: 49 percent of the lowest-income communities had no ICU beds in their communities, compared to only 3 percent of the highest income areas. Conversely, 46 percent of the lowest-income communities had an ICU bed supply of more than four beds per ten thousand residents age fifty or older, while a total of 59 percent of the highest-income places had more than four beds per ten thousand.

These differences were most pronounced in rural areas. Similar proportions of low-, middle-, and high-income communities in cities had access to more than seven ICU beds per ten thousand residents age fifty or older, compared with communities in less urban areas.

In response to these disparities, the study’s authors suggest several steps that policymakers might take to mitigate further harms of COVID-19 in these regions. First, they point out that individual hospitals facing severe COVID-19-related financial losses have little incentive to attract critically-ill patients from underserved areas, as these patients often lack extensive insurance coverage, and the costs of their care often exceed reimbursement rates. Therefore, the authors recommend that higher-level coordination is needed at the county, state, and federal levels to facilitate hospital sharing of the demand for care and to publicly finance specialized resources, such as ventilators and critical care doctors.

Second, the researchers say that the typical emergency medical system guideline to “transport to the nearest hospital” should be revisited under these new pandemic conditions. Local emergency medical services agencies should develop plans for how and under what conditions patients can be transported to hospitals outside their immediate communities and how these transport protocols will be communicated to the public.

And lastly, the study’s authors argue that emergency funds need to be directed toward hospitals lacking sufficient ICU resources, especially those caring for large older populations that are more likely to be hospitalized for COVID-19.

“I hope our study provides policymakers with information on which communities will be in greatest need, as well as guidance in the steps required to meet those needs,” Kanter said.

Additional Penn authors of this study are Andrea G. Segal and Peter W. Groeneveld.

If our reporting has informed or inspired you, please consider making a donation. Every contribution, no matter the size, empowers us to continue delivering accurate, engaging, and trustworthy science and medical news. Independent journalism requires time, effort, and resources—your support ensures we can keep uncovering the stories that matter most to you.

Join us in making knowledge accessible and impactful. Thank you for standing with us!