The old saying may ring true: You are what you eat. There is new evidence that the gut is linked to brain health, thanks to a bacterium-derived compound known as indole, according to an international team of researchers.

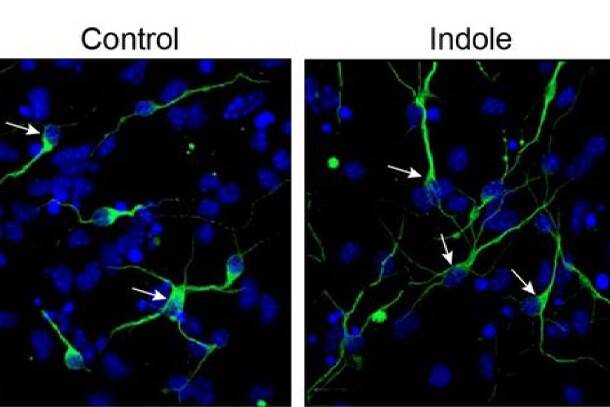

In a July 1 Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS) paper, researchers show the molecule indole stimulates brain cell growth in the hippocampus, the brain structure in charge of learning and memory. The amino acid tryptophan, which produces indole, comes from eating foods like turkey, leafy greens and broccoli.

Indole’s benefits go beyond brain cell growth, according to co-author Thomas Wood, Biotechnology Endowed Chair and professor of chemical engineering in the Penn State College of Engineering.

“Indole can influence mood, decrease tissue damage and aging, protect the skin and liver, and help alleviate some of the symptoms of Crohn’s disease, gastro-intestinal dysfunction, and brain-related conditions like Alzheimer’s disease,” Wood said. “Those are pretty impactful benefits coming from a bacteria-derived compound, and it is fascinating that bacteria and human cells communicate in this way.”

When we eat food, Wood explained, the good bacteria in our gut convert the tryptophan into indole, which can pass through the blood-brain barrier and positively impact the brain and other areas of the body.

“We all have about a half pound of bacteria in our digestive systems,” Wood said, “And it’s a symbiotic relationship. But we still have limited knowledge on the good gut bacteria and what it does. In the case of indole, however, we now understand that it is used by human cells, that it does all these different things for us, and that it makes us better.”

The research builds upon a 2010 PNAS paper, which found indole tightens epithelial cell junctions and prevents pathogens from entering the blood stream.

Earlier research has also shown that indole derivatives can attack bacterial infections after traditional antibiotics have failed. Wood’s team at Penn State found an indole derivative that kills the pathogens Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Staphylococcus aureus while they are dormant.

“Indole can target non-growing bacteria, as in the case of pseudomonas infections in burn patients or cystic fibrosis sufferers,” Wood said. “Antibiotics are designed to target fast-growing bacteria, which doesn’t help those with non-growing bacteria that often survive antibiotic treatments by sleeping through them.”

Indole-derived treatments that target non-growing bacterial infections could become a clinical treatment in the future. But therapeutic measures for the adult brain, particularly through dietary changes, could be more immediate.

“This finding provides an explanation of how gut-brain communication is translated into brain cell renewal, through gut microbe-produced molecules stimulating the formation of new nerve cells in the adult brain,” said principal investigator Sven Pettersson, of the National Neuroscience Institute of Singapore, in a news release. “These findings bring us closer to the possibility of novel treatment options to slow down memory loss, [including] designing dietary intervention using food products enriched with indoles as a preventive measure to slow down aging.”

If our reporting has informed or inspired you, please consider making a donation. Every contribution, no matter the size, empowers us to continue delivering accurate, engaging, and trustworthy science and medical news. Independent journalism requires time, effort, and resources—your support ensures we can keep uncovering the stories that matter most to you.

Join us in making knowledge accessible and impactful. Thank you for standing with us!