The tiny minority of state-educated students who take Ancient History at GCSE worry that the subject’s exclusive reputation will brand them ‘elitist’ in the eyes of friends and relatives, research suggests.

Their perspectives are documented in a newly-published study, which argues that Ancient History’s position as a minority subject in the curriculum is reinforcing its image as the preserve of a privileged elite. Since 2009, any school in England, Wales and Northern Ireland has had the option to offer Ancient History GCSE, but very few do so. Fewer than 1,000 candidates (about 0.1%) sit the exam every year, and only a fraction are from state schools.

The study, by academics at the University of Cambridge, surveyed students at three state-funded comprehensive schools which do teach the subject. All of the students said they felt stigmatised by their peers for taking Ancient History, and that it was generally perceived as “posh”, “academic”, “boring”, “elitist” and “snobby”. Some said these views were shared by members of their own family.

The researchers argue that making Ancient History more widely available in schools would resolve this image problem. There is also some evidence that it might even be a popular move. Despite their concerns, students who took the subject also said they found it interesting and rewarding. Many were particularly interested in the stranger and more distant aspects of the ancient world.

Dr Frances Foster, from the Faculty of Education, University of Cambridge, said: “These were three very different schools, in very different communities and with varying levels of deprivation, but every single student we spoke to had experienced resistance to the idea of studying Ancient History from relatives or friends.”

“The message we got was generally: ‘This is really cool stuff, but it’s not meant for people like us.’ Once they stepped outside the classroom, they were uncomfortable even disclosing that they did Ancient History because they were worried about being seen as different, or about people assuming they went to a posh school. We ought to be emphasising that they have a right to study this subject just as much as anyone.”

The students were asked to answer a questionnaire about their background and any opportunities they had to learn about Ancient History outside school (for example by visiting museums). They then took part in a series of semi-structured interviews and focus groups, which explored their feelings about the subject.

Their comments disclosed widespread discomfort with being given what they knew was unequal access to a subject associated with social privilege. In many cases, either the students, or their relatives and peers, appeared to view Ancient History as both ‘very academic’ and ‘prestigious’ specifically because so few people study it.

One interviewee told the researchers: “People perceive it as posh because it’s not common… a lot of private schools have the option of taking it but I don’t know any other school in this area that has Latin or Ancient History.” Another said: “It’s perceived as quite an intelligent subject because a lot of schools don’t offer it. When you say, ‘I do Ancient History’, people kind of judge you and think, oh, you must go to a posh school.”

Many students were aware that this was a misconception, but they consistently felt that by taking the subject they had nonetheless been branded “clever”, “upper class” or even “unlucky” by their peers.

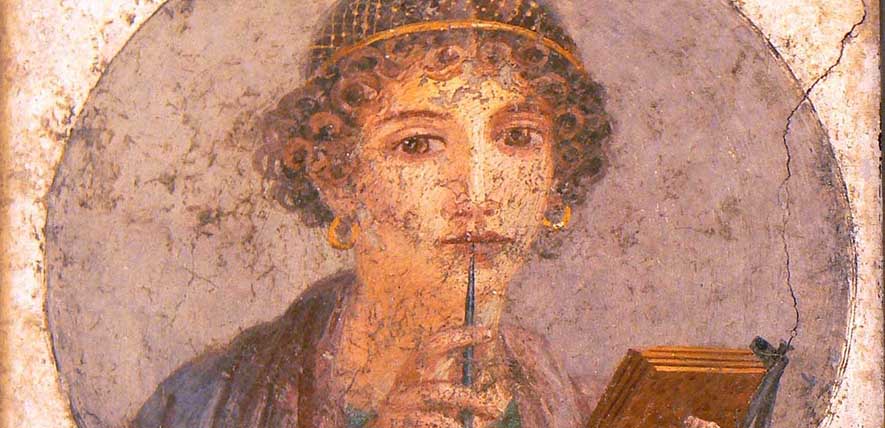

Despite this, many also expressed considerable interest in various source materials, the age of the subject matter, and the sophistication of the ancient world. The study also explores cases such as that of a girl from a Middle Eastern Family who explained how she had been able to feel more connected to her own heritage through learning about the Persian Empire. Two other students spoke enthusiastically about how the ancient world had inspired Winston Churchill during his own political career.

“They were really interested that texts which had survived for two millennia might still be useful to governments in another time and country,” Foster said. “Part of Ancient History’s attraction for students seems to be that the stories and objects they are studying were features of people’s lives two thousand years ago, but have come down to us. Another part is the very different nature of societies in the ancient world – the fact that so much of it is just plain weird.”

All the students said they would feel more comfortable taking Ancient History if it was more widely available. As the study’s authors note, several organisations – including the Classical Association, Classics for All, and the University’s own Cambridge Schools Classics Project – have actively campaigned for some time to increase access to Ancient History partly because of concerns about its marginal status.

Their report also points out that, because the GCSE course does not require knowledge of ancient languages, it can be delivered by History teachers even in schools which do not teach Classics.

“At the moment young people’s access to the ancient world is defined largely by chance – whether or not their school happens to offer it,” Foster said. “As long as that remains the case, students will be told it’s not for them, it’s not going to get them a job, and they would be better off doing something else. Ancient History was put on the GCSE curriculum to make it more accessible. If we value that principle, we should be worried that so many of the students who actually get to study it feel so uncomfortable about the idea.”

The study is published open access in The Curriculum Journal.

If our reporting has informed or inspired you, please consider making a donation. Every contribution, no matter the size, empowers us to continue delivering accurate, engaging, and trustworthy science and medical news. Independent journalism requires time, effort, and resources—your support ensures we can keep uncovering the stories that matter most to you.

Join us in making knowledge accessible and impactful. Thank you for standing with us!