When a Southwest Research Institute scientist discovered surprising evidence that Saturn’s smallest, innermost moon could generate the right amount of heat to support a liquid internal ocean, colleagues began studying Mimas’ surface to understand how its interior may have evolved.

Numerical simulations of the moon’s Herschel impact basin, the most striking feature on its heavily cratered surface, determined that the basin’s structure and the lack of tectonics on Mimas are compatible with a thinning ice shell and geologically young ocean.

“In the waning days of NASA’s Cassini mission to Saturn, the spacecraft identified a curious libration, or oscillation, in Mimas’ rotation, which often points to a geologically active body able to support an internal ocean,” said SwRI’s Dr. Alyssa Rhoden, a specialist in the geophysics of icy satellites, particularly those containing oceans, and the evolution of giant planet satellite systems. She is the second author of a new Geophysical Research Letters paper on the subject. “Mimas seemed like an unlikely candidate, with its icy, heavily cratered surface marked by one giant impact crater that makes the small moon look much like the Death Star from Star Wars. If Mimas has an ocean, it represents a new class of small, ‘stealth’ ocean worlds with surfaces that do not betray the ocean’s existence.”

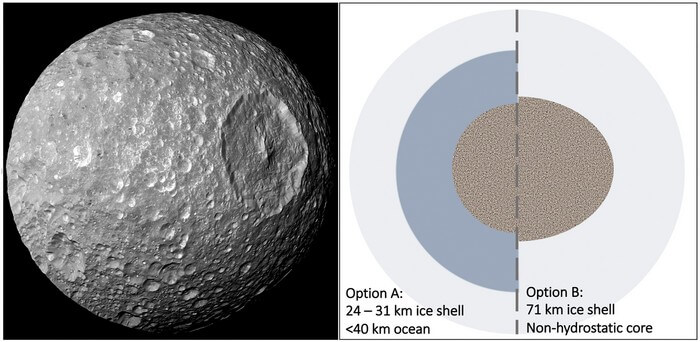

Rhoden worked with Purdue graduate student Adeene Denton to better understand how a heavily cratered moon like Mimas could possess an internal ocean. Denton modeled the formation of the Hershel impact basin using iSALE-2D simulation software. The models showed that Mimas’ ice shell had to be at least 34 miles (55 km) thick at the time of the Herschel-forming impact. In contrast, observations of Mimas and models of its internal heating limit the present-day ice shell thickness to less than 19 miles (30 km) thick, if it currently harbors an ocean. These results imply that a present-day ocean within Mimas must have been warming and expanding since the basin formed. It is also possible that Mimas was entirely frozen both at the time of the Herschel impact and at present. However, Denton found that including an interior ocean in impact models helped produce the shape of the basin.

“We found that Herschel could not have formed in an ice shell at the present-day thickness without obliterating the ice shell at the impact site,” said Denton, who is now a post-doctoral researcher at the University of Arizona. “If Mimas has an ocean today, the ice shell has been thinning since the formation of Herschel, which could also explain the lack of fractures on Mimas. If Mimas is an emerging ocean world, that places important constraints on the formation, evolution and habitability of all of the mid-sized moons of Saturn.”

“Although our results support a present-day ocean within Mimas, it is challenging to reconcile the moon’s orbital and geologic characteristics with our current understanding of its thermal-orbital evolution,” Rhoden said. “Evaluating Mimas’ status as an ocean moon would benchmark models of its formation and evolution. This would help us better understand Saturn’s rings and mid-sized moons as well as the prevalence of potentially habitable ocean moons, particularly at Uranus. Mimas is a compelling target for continued investigation.”

Rhoden is co-leader of NASA’s Network for Ocean Worlds Research Coordination Network and previously served on the National Academies’ Committee on Astrobiology and Planetary Science. A paper describing this research was published online in GRL and can be accessed at https://agupubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1029/2022GL100516

For more information, visit https://www.swri.org/planetary-science.

If our reporting has informed or inspired you, please consider making a donation. Every contribution, no matter the size, empowers us to continue delivering accurate, engaging, and trustworthy science and medical news. Independent journalism requires time, effort, and resources—your support ensures we can keep uncovering the stories that matter most to you.

Join us in making knowledge accessible and impactful. Thank you for standing with us!