Researchers from the University of Sydney and Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine have identified a promising new treatment for cobra bites using a widely available and inexpensive drug. The study, published in Science Translational Medicine, reveals that heparin, a common blood thinner, could significantly reduce the devastating tissue damage caused by cobra venom.

Unraveling the Cobra’s Deadly Bite

Cobra bites pose a significant health threat worldwide, causing thousands of deaths annually and leaving many more victims with severe injuries. The venom’s necrotic effects can lead to amputation and lifelong disability. Current antivenom treatments, while life-saving, often fail to prevent this localized tissue damage.

Professor Greg Neely from the University of Sydney, a corresponding author of the study, explains: “Our discovery could drastically reduce the terrible injuries from necrosis caused by cobra bites – and it might also slow the venom, which could improve survival rates.”

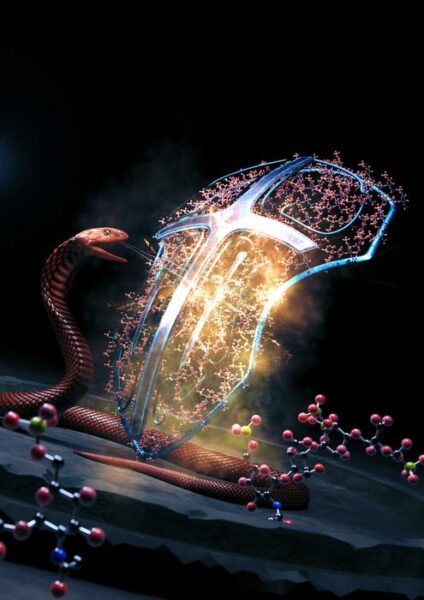

The research team used CRISPR gene-editing technology to identify the human genes targeted by cobra venom. They discovered that the venom interacts with enzymes involved in producing heparan and heparin, molecules found on cell surfaces and released during immune responses.

Heparin: A ‘Decoy’ Antidote

Armed with this knowledge, the researchers tested heparin and related drugs as potential antidotes. These compounds act as ‘decoys,’ binding to and neutralizing the tissue-damaging toxins in cobra venom.

PhD student and lead author Tian Du emphasizes the potential impact: “Heparin is inexpensive, ubiquitous and a World Health Organization-listed Essential Medicine. After successful human trials, it could be rolled out relatively quickly to become a cheap, safe and effective drug for treating cobra bites.”

This approach represents a significant advancement over current antivenoms, which are based on 19th-century technologies. The heparinoid drugs offer a more targeted and potentially more effective treatment for the localized effects of cobra bites.

Professor Nicholas Casewell, Head of the Centre for Snakebite Research & Interventions at Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine, highlights the importance of this discovery: “Our findings are exciting because current antivenoms are largely ineffective against severe local envenoming, which involves painful progressive swelling, blistering and/or tissue necrosis around the bite site. This can lead to loss of limb function, amputation and lifelong disability.”

Why it matters: Snakebites affect up to 5.4 million people annually, with up to 138,000 deaths and 400,000 cases of long-term disability. Cobras are responsible for a significant portion of these incidents in parts of India and Africa. The World Health Organization has set an ambitious goal of halving the global burden of snakebite by 2030. This new antidote could play a crucial role in achieving this target, especially in low- and middle-income countries where access to effective treatments is limited.

The potential of heparin as a cobra bite antidote raises several questions. Will it be effective against all cobra species? How soon could human trials begin? Could this approach be applied to other venomous snakes?

Looking ahead, this research opens up new possibilities for snakebite treatment. The team’s systematic approach to identifying venom antidotes using CRISPR technology could lead to discoveries for other dangerous venoms. In 2019, the same team identified an antidote to box jellyfish venom using similar methods.

As the global community races to meet the WHO’s 2030 goal for reducing snakebite impact, this discovery offers hope for more effective, accessible treatments. Professor Neely concludes: “We hope that the new cobra antidote we found can assist in the global fight to reduce death and injury from snakebite in some of the world’s poorest communities.”

The next steps will likely involve human trials to confirm the safety and efficacy of heparin as a cobra bite treatment. If successful, this could revolutionize snakebite care, particularly in rural areas where access to traditional antivenoms is limited. The low cost and wide availability of heparin could make it a game-changer in the fight against one of the world’s most neglected tropical diseases.

If our reporting has informed or inspired you, please consider making a donation. Every contribution, no matter the size, empowers us to continue delivering accurate, engaging, and trustworthy science and medical news. Independent journalism requires time, effort, and resources—your support ensures we can keep uncovering the stories that matter most to you.

Join us in making knowledge accessible and impactful. Thank you for standing with us!