To understand a country, it helps to know its schools. To grasp Mexico, MIT historian Tanalís Padilla believes, that means learning about its rural “normales,” teacher-training schools with outsized historical influence on the country’s politics.

This might seem surprising. At its height, the system of rural normales consisted of only 35 such boarding schools, scattered in the countryside, populated by the children of peasants and indigenous residents. Yet these schools had been founded on the ideals of the Mexican Revolution of the 1910s, which promised justice for the poor, land reform, workers’ rights, and education. The normales turned out to be among the places where those ideals were taken most seriously.

“Their legacy is really profound,” says Padilla, a professor of history at MIT. At normales, she adds, from their creation in the 1920s onward, “Teachers were not just supposed to teach students to read and write, but also teach them about their rights — their rights to land, their right to form unions, to education. The schools wanted to form the students to be leaders.”

Rather than simply inculcating loyalty to the Mexican state and its policies, these schools churned out generations of activists working to realize the unfulfilled promises of Mexico’s revolutionary moment.

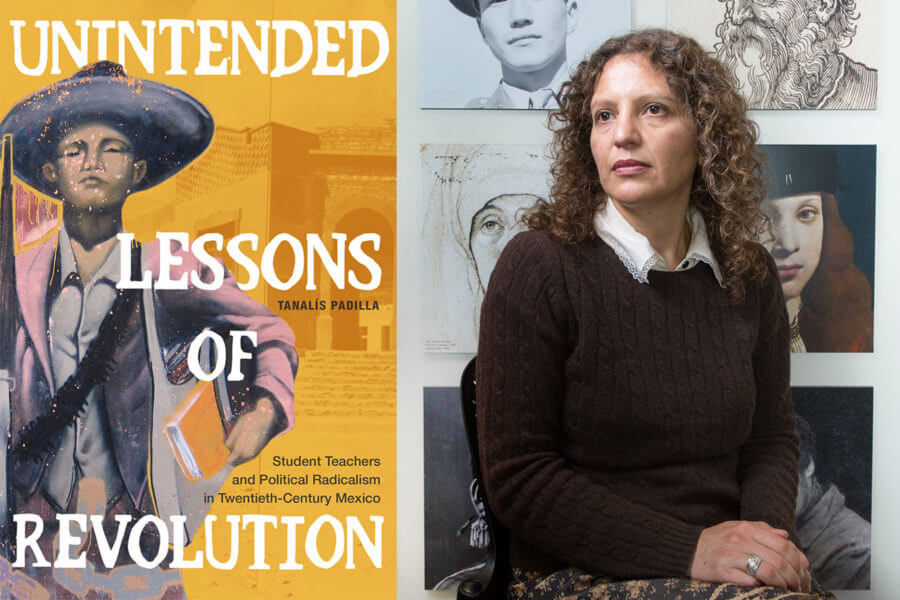

“The very schools meant to shape a loyal citizenry became hotbeds of radicalism,” Padilla writes in a new book on the subject, “Unintended Lessons of Revolution: Student Teachers and Political Radicalism in Twentieth-Century Mexico,” just published by Duke University Press.

“Their perspective, their struggle, brings into sharp relief the power relations

that created the past and produced the present,” Padilla writes. That present includes the 2014 kidnapping and disappearance of 43 protesting normalista students from Ayotzinapa, an event that generated headlines and protests, and tragically underscored the ongoing salience of the schools in the country’s political disputes.

Action learning

The origins of Padilla’s new book lie partly in her 2008 book, “Rural Resistance in the Land of Zapata,” which examined agrarian uprisings in midcentury Mexico.

“Throughout my research on the peasant movement, I kept [noticing] the role of rural teachers,” Padilla says. “Earlier works assumed rural teachers were agents of state consolidation, sent to the four corners of the country to instill patriotism to the Mexican nation. But I came across these schools that had a very radical tradition, based on [promises] of the Mexican state. I wanted to study how these schools came to be.”

Padilla’s research draws on many kinds of archival sources, as well as interviews with students and teachers. Her work establishes a chronology for the schools that reflects the contours of Mexican politics over the last century. Founded in the 1920s, the normales grew and flourished in the 1930s under the reform-minded presidency of Lázaro Cárdenas. Abetted by an undersecretary of education named Moisés Sáenz, who had studied with John Dewey at Columbia University, the normales emphasized an “action pedagogy” and learning by doing.

“The schools gave students a big say in running the schools themselves,” Padilla says. “A lot of student activism leads to skills — public speaking, how to organize a meeting, how to mobilize people, how to get on a bus and talk to people. These skills become valuable later on for leadership, and this is one of the ways the graduates of these normales are different than graduates from other schools. Everyone says that, even opponents who want to co-opt the schools.”

A conservative turn in the 1940s decreased state support for the rural normales as institutions, and by the 1970s their numbers had decreased to 15, about where they remain today. Still, through the decades, where reform movements have occurred in Mexico, students from the rural normales have often been involved.

“They have an outsized role in political movements,” Padilla says. At the same time, she acknowledges, not every last graduate of a rural normale became a leftist organizer: “The legacy of these schools is based on radical politics, but once students graduate, you have a full gamut of [life trajectories]. Some people remain committed to teaching, others take seriously being activists, and some will go on to be conservative officials in party politics.”

Still, as much as some conservatives in Mexico might like to shutter the normales, it has never happened, due to the activism of their students.

“They’re a really important safety net, and that’s one reason why they’re so valued to the rural population,” Padilla says. “While there is poverty in Mexico, these schools will continue to have a reason to exist.”

Broader themes

In reconstructing the history of 35 teacher-training schools, Padilla’s work uses that narrower slice of history to get at larger ideas. One such theme is thinking of the Mexican revolution as unfinished business, a movement that has only delivered part of what it promised to the masses, with political fractures stemming from that situation.

Another, related point involves questioning the vaunted political stability of Mexico and its long-term one-party system. “For a long time scholars thought of Mexico as the most stable Latin American country,” Padilla says. Instead, she prefers to focus on the struggles to change the country, in the wake of “the abandoning of the revolutionary reforms which were the constituting elements of modern Mexico,” as she puts it.

Still one more theme of Padilla’s work involves the centrality of rural and agrarian life to the country’s politics. Mexico has become quite urbanized in the postwar era, and some political events, like the protests of 1968, are thought of as urban events. But, as Padilla details in one chapter of the book, student protests in the 1960s were much more heavily rural than people now realize, and often preceded 1968 — with a rural normale influence, of course.

“Unintended Lessons of Revolution” has received praise from other scholars in the field. Brooke Larson, a professor of history at Stony Brook University, calls the book “a tremendously impressive study of the rural normal school,” adding that it casts “new light on a series of larger questions concerning Mexico’s legacy of revolution, its failed rural policies, and the explosion of unrest among rural teachers and activists.”

For her part, Padilla says she hopes readers will both reflect on Mexican history and relate her narrative to other countries where similar issues pertain.

“The book is both specific to Mexico, and also universal, where it relates to the effects of the power of education,” Padilla says. “Education is not just reading and writing or [training for] a profession, but understanding the world around you. Historically, education can be assimilationist, forming loyalty to a country, but it can also have liberatory qualities. These schools speak to the power, and potentially liberatory power, of education.”