A new study has provided direct evidence that serotonin release is disrupted in the brains of people with depression.

Depression is a common mental illness that affects people worldwide and is often treated with medications that target the serotonin signaling system. However, these medications only work for about half of patients and fewer than 30% experience complete recovery. By understanding more about serotonin’s role in depression, researchers may be able to develop more effective treatments.

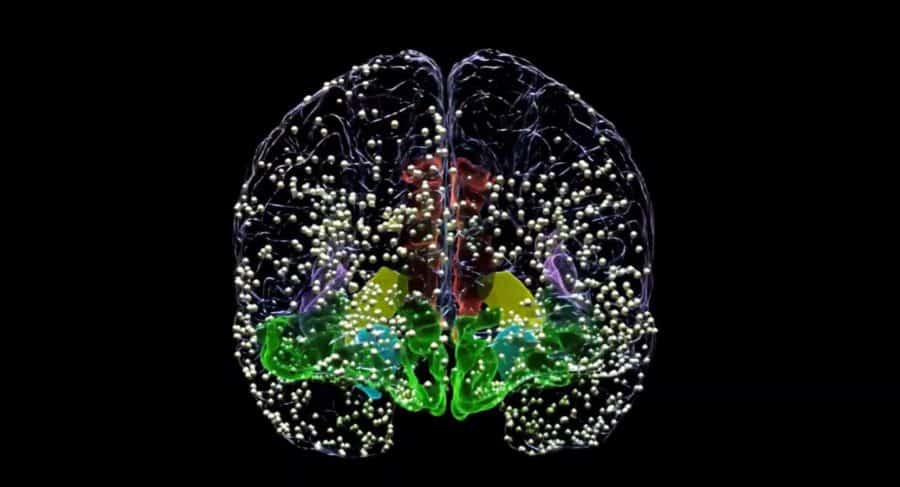

The study used a new imaging technique to compare serotonin release in 17 people with depression and 20 healthy individuals. The researchers found that people with depression had a blunted capacity for serotonin release in certain brain regions. The study did not find a relationship between the severity of depression and the extent of serotonin release deficits.

Serotonin is a neurotransmitter, or chemical messenger, that helps transmit signals between brain cells. It is involved in various functions, including mood, sleep, and appetite. Researchers have long thought that disruptions in the serotonin system may be involved in major depression. However, previous research has not provided direct evidence of this. The new study, published in Biological Psychiatry, sought to address this gap in knowledge.

The study was conducted by Invicro, a global imaging contract research organization, in collaboration with researchers from several universities. The researchers used a novel imaging technique called positron emission tomography (PET) to look at serotonin release in response to a pharmacological challenge. They gave both the people with depression and the healthy individuals a dose of a stimulant drug that increases serotonin levels. They then used PET scans to measure the binding of a radioligand called [11C]Cimbi-36 to serotonin receptors in the brain. The binding of the radioligand can be used as an indicator of serotonin levels.

The researchers found that, in healthy individuals, the binding of the radioligand decreased significantly after the drug was given, indicating an increase in serotonin levels. However, in people with depression, the binding did not decrease significantly, suggesting a blunted capacity for serotonin release in certain brain regions. The study did not find a relationship between the severity of depression and the extent of serotonin release deficits.

The results of the study provide important new support for further exploration of the role of serotonin in depression. This is particularly timely, as drugs that target serotonin receptors, such as psychedelics, are being studied as potential treatments for mood disorders. The imaging method used in the study, in combination with similar methods for other brain systems, has the potential to help researchers better understand the varied responses of people with depression to antidepressant medication. By understanding more about how these medications work, researchers may be able to develop more effective treatments for depression.

If our reporting has informed or inspired you, please consider making a donation. Every contribution, no matter the size, empowers us to continue delivering accurate, engaging, and trustworthy science and medical news. Independent journalism requires time, effort, and resources—your support ensures we can keep uncovering the stories that matter most to you.

Join us in making knowledge accessible and impactful. Thank you for standing with us!