Headline: Whale Echolocation Organs Traced Back to Jaw Muscles and Bone Marrow, Study Suggests

A new study has found that the fatty tissues that allow dolphins and whales to use sound for communication, navigation, and hunting may have evolved from the muscles and bone marrow in their jaws.

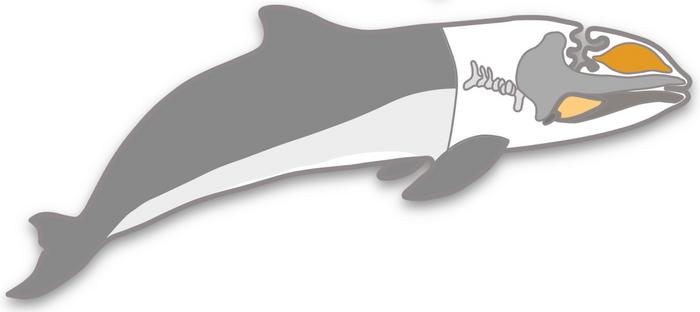

Researchers at Hokkaido University in Japan looked at the DNA of genes that were active in the acoustic fat bodies of harbor porpoises and Pacific white-sided dolphins. These fat bodies are found in three places: the melon (in the forehead), alongside the jawbone (extramandibular fat bodies or EMFBs), and inside the jawbone (intramandibular fat bodies or IMFBs).

The evolution of these acoustic fat bodies was crucial for toothed whales to develop echolocation, which helps them navigate underwater. However, not much is known about how these fatty tissues originated.

“Toothed whales have undergone significant degenerations and adaptations to their aquatic lifestyle,” said Hayate Takeuchi, a PhD student at Hokkaido University’s Hayakawa Lab and the lead author of the study. One of these adaptations was a partial loss of their sense of smell and taste, while gaining echolocation abilities.

The researchers discovered that genes typically associated with muscle function and development were active in the melon and EMFBs. They also found evidence suggesting that the extramandibular fat evolved from the masseter muscle, which connects the lower jawbone to the cheekbones in humans and is important for chewing.

Assistant Professor Takashi Hayakawa, who led the study, explained, “This study has revealed that the evolutionary tradeoff of masticatory muscles for the EMFB—between auditory and feeding ecology—was crucial in the aquatic adaptation of toothed whales. It was part of the evolutionary shift away from chewing to simply swallowing food, which meant the chewing muscles were no longer needed.”

When analyzing gene expression in the intramandibular fat, the researchers detected activity of genes related to immune functions, such as activating parts of the immune response and regulating the formation of T cells (a type of white blood cell).

The Stranding Network Hokkaido (SNH) played a vital role in this research by collecting samples from stranded whales found on the shores and river mouths of Hokkaido, Japan. “Long-term communication with local people and communities in Hokkaido has enabled researchers to conduct various studies of whale biology, including our surprising findings,” said Professor Takashi Fritz Matsuishi, the director of SNH.

This study sheds new light on how toothed whales adapted to their underwater environment by repurposing jaw muscles and bone marrow into specialized fatty tissues for echolocation. The findings contribute to our understanding of the evolutionary history of these fascinating marine mammals and highlight the importance of collaborative efforts between researchers and local communities in advancing scientific knowledge.

If our reporting has informed or inspired you, please consider making a donation. Every contribution, no matter the size, empowers us to continue delivering accurate, engaging, and trustworthy science and medical news. Independent journalism requires time, effort, and resources—your support ensures we can keep uncovering the stories that matter most to you.

Join us in making knowledge accessible and impactful. Thank you for standing with us!