Scientists from Canada and China have unveiled an extraordinary fossil dating back approximately 125 million years, capturing a pivotal moment when a carnivorous mammal attacked a larger plant-eating dinosaur. The unique fossil sheds light on predatory behavior by mammals towards dinosaurs, challenging the prevailing belief that dinosaurs faced minimal threats from their mammalian counterparts during the Cretaceous period. The study, published today in the journal Scientific Reports, is co-authored by Dr. Jordan Mallon, a paleobiologist from the Canadian Museum of Nature.

Dr. Mallon describes the fossil as a portrayal of “the two animals…locked in mortal combat, intimately intertwined,” emphasizing its significance in providing evidence of mammalian predatory actions against dinosaurs. The fossil, now housed in the Weihai Ziguang Shi Yan School Museum in China’s Shandong Province, contradicts previous assumptions and indicates that mammals played a more active role in the ecosystem during the Cretaceous era when dinosaurs were dominant.

The fossilized specimen features a well-preserved dinosaur, identified as a Psittacosaurus species, which was roughly the size of a large dog. Psittacosaurs were herbivorous horned dinosaurs that lived in Asia from 125 to 105 million years ago. Accompanying the Psittacosaurus is the remains of a badger-like mammal called Repenomamus robustus. Despite being relatively small compared to dinosaurs, Repenomamus was one of the largest mammals of the time, preceding the eventual domination of mammals on Earth.

Before this discovery, paleontologists were aware of Repenomamus preying on dinosaurs, including Psittacosaurus, based on the presence of fossilized baby Psittacosaurus bones found in the mammal’s stomach. Dr. Mallon explains that while the coexistence of these two animals was already known, the unique aspect of this remarkable fossil is the evidence it provides of predatory behavior.

The fossil was unearthed in China’s Liaoning Province in 2012 and includes nearly complete skeletons of both the Psittacosaurus and Repenomamus. The fossils’ remarkable state of preservation is attributed to their origin in the Liujitun fossil beds, dubbed “China’s Dinosaur Pompeii.” This name alludes to the site’s abundant collection of dinosaur, small mammal, lizard, and amphibian fossils, which were rapidly buried by mudslides and debris following volcanic eruptions. Mineralogist Dr. Aaron Lussier from the Canadian Museum of Nature confirmed the presence of volcanic material in the rock matrix of the fossil through analysis.

The Psittacosaurus-Repenomamus fossil was under the care of Dr. Gang Han in China, who brought it to the attention of Dr. Xiao-Chun Wu, a paleobiologist at the Canadian Museum of Nature. Dr. Wu, having collaborated with Chinese researchers for many years, recognized the fossil’s significance upon first seeing it.

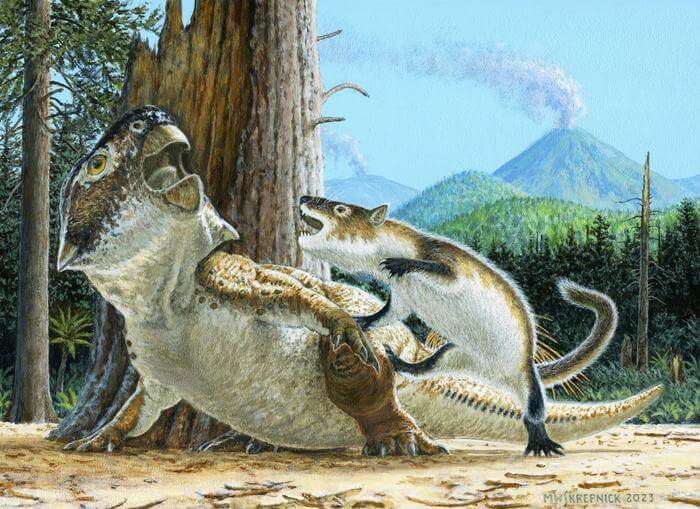

Upon close examination, it is evident that the Psittacosaurus lies prone, with its hindlimbs folded on either side of its body. The Repenomamus coils to the right and perches atop its prey, gripping the larger dinosaur’s jaw and biting into its ribs. Dr. Mallon notes that the positioning and interaction of the two animals strongly suggest an ongoing attack.

The research team, including Mallon, Wu, and their colleagues, dismissed the possibility of the mammal merely scavenging a deceased dinosaur. Lack of tooth marks on the dinosaur’s bones indicates that scavenging did not occur, supporting the hypothesis of predation. Furthermore, the entanglement between the two creatures implies that the dinosaur was not dead before the mammal’s arrival. The positioning of Repenomamus above the Psittacosaurus further indicates the mammal’s role as the aggressor.

Drawing parallels to modern-day occurrences of smaller animals hunting larger prey, Mallon and Wu mention that lone wolverines have been observed hunting larger animals such as caribou and domestic sheep. Similarly, wild dogs, jackals, and hyenas on the African savanna attack live prey, often causing them to collapse in shock.

Mallon suggests that the fossil depicts a similar scenario, with Repenomamus consuming the Psittacosaurus while it was still alive, before both creatures met their demise in the aftermath of the volcanic events. The researchers anticipate that the Lujiatun fossil beds’ volcanic deposits in China will continue to yield new evidence of species interactions previously unknown in the fossil record, as outlined in their scientific paper.

If our reporting has informed or inspired you, please consider making a donation. Every contribution, no matter the size, empowers us to continue delivering accurate, engaging, and trustworthy science and medical news. Independent journalism requires time, effort, and resources—your support ensures we can keep uncovering the stories that matter most to you.

Join us in making knowledge accessible and impactful. Thank you for standing with us!